COLUMN: Between Languages: A conversation with Gabriel Cholette

"I learned to write on Grindr"

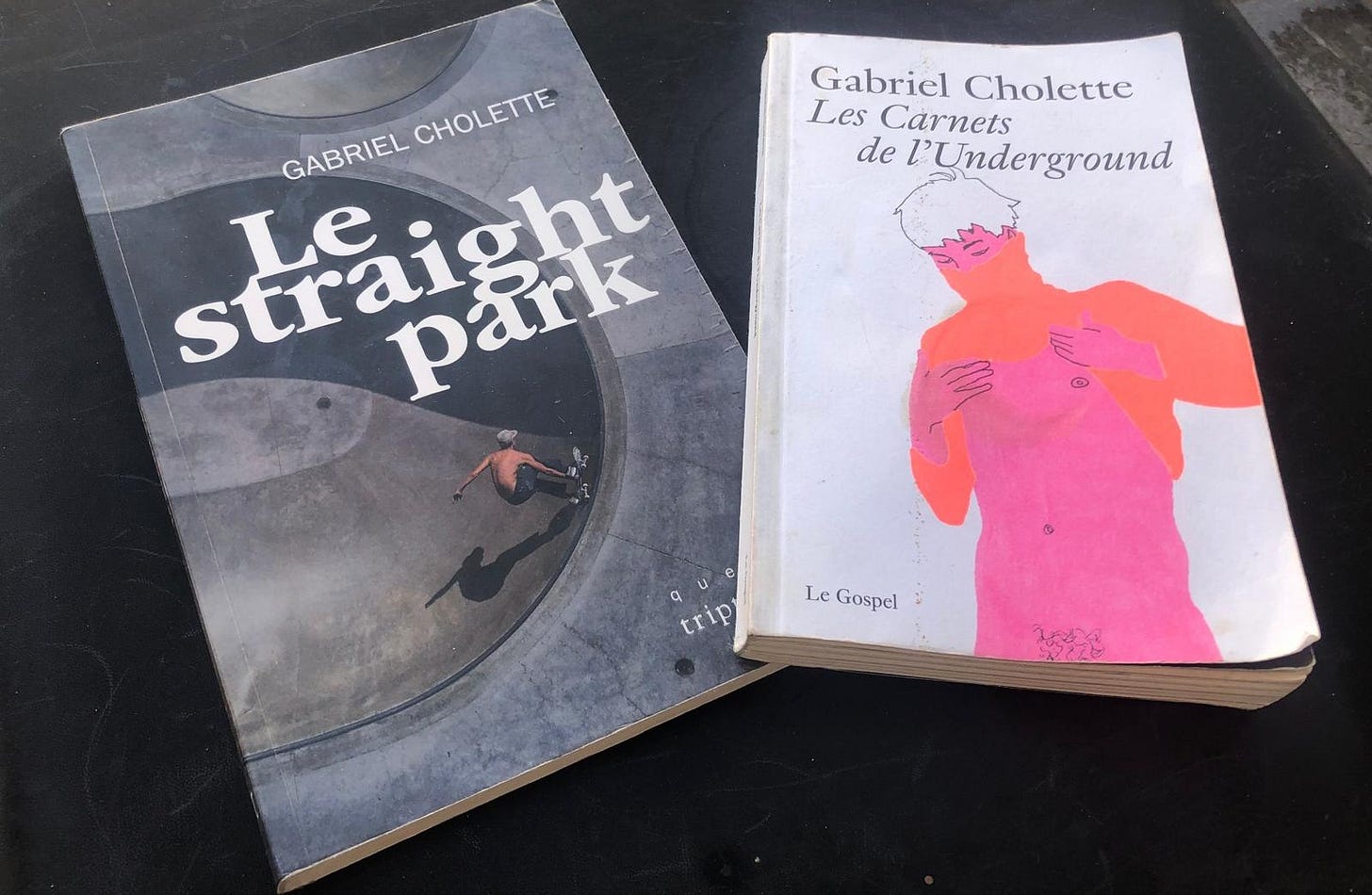

I think I have a fetish for dying industries. At least, my initial choice of translation as a career, and my interest in books, seems to suggest that. When I initially became a translator I did so sort of cynically, jumping into commercial translation just because as someone who wanted to be an artist, it was a gig I saw and thought, ‘I guess I could do that.’ I’ve often envied people for whom it is a passion. But translating something like this, this interview I conducted in French with Quebecois writer Gabriel Cholette, is nothing but pleasurable, and it makes me understand those people better. We spoke about living and thinking in between two different languages and the strangeness of inhabiting that sort of interstitial space. While we were talking I thought, this is exactly the kinds of conversations I want to be having more of in my life. Lucky for me, this is the first in what I hope will be a series of many conversations with authors who think and write between English and another language. I first came into Gabriel’s work knowing nothing about it when, at a book festival in Paris, a bookseller recommended Notes from the Underground, his first book, to me. He said it was about partying & hooking up & doing drugs & looking for love in Berlin, and it did not disappoint. I read it in French, but it is also available in English. After reading and also greatly enjoying his second book, Le Straight Park, which takes a queer look at skate parks/culture, and noting that both books, while in French, heavily feature English and do a lot of thinking between the two languages, I thought, ‘Ok, I need to talk to this guy.’ So we met on Zoom – him in Montreal, and me in Paris – and had the following conversation. Incidentally, over the course of it I learned that while the first book is available in English, the second one hasn’t been slated for translation yet. But if you’re an English language publisher and this conversation is making you think ‘Hey, someone should really translate that gay skating book…’ – feel free to hit me up.

Oscar d’Artois: So, are you from Montreal?

Gabriel Cholette: Yes, I'm from Saint Michel originally, a working class area in the north of the city. Now I live in Verdun, an out-of-the-way neighborhood where misfits live.

O: And you have two books, when did they come out?

G: Notes from the Underground came out in 2021, then in English in 2022, and in France in 2023. And Le Straight Park came out in 2024.

O: So, you're on a roll.

G: Yes, one book coming out a year, sort of.

O: Is French your native language?

G: Yes.

O: But you clearly speak fluent English.

G: Yes. I've dated in English a lot. I learned English through pillow talk, dating guys. It was my love language, I think. I liked cruising in English, too. Because of my personality in French, since I was raised in it. Well, it was more than that. English gave me this freedom to explore. Find novelty. It gave me a new personality. I've always found English sort of charming. It was the language of the TV shows I watched, like Skins.

O: Skins! So, you got comfortable in the language by talking to guys. But you must have been exposed to it before that?

G: Well, I did my CEGEP, the 2 years of pre-university education we have here, in English. I was just curious about English. I studied film there. There was something romantic about my relationship to English, to do with pop culture, which I was really into. But now I'm in this phase of going back to French, because my boyfriend is Belgian and hangs out with a lot of French people, so I'm rekindling my love for French. And I'm getting really into French chanson, which I didn't know much about, because I was really into pop divas like Beyoncé, Miley Cyrus...

O: Yes, Miley's in your book! How did the internet in general impact your first encounters with English?

G: I was really fascinated by my phone when I was 14-15. I created a fake credit card in my parents' name to get my first one. For a long time, my iPhone 3 was my most cherished possession. I'd go on sites like Imgur a ton. In terms of music, too, I remember with my mom we'd listen to things like Britney Spears, and then translate the lyrics into French, like Oops I did it again! became Oups! Je l'ai fait encore. I'd be on my mom's lap translating this stuff...

O: And you say you're rekindling your relationship with French, but you did write both your books in French.

G: Yeah. All the music I listened to for a while was anglophone, American music. I became a bit closed off even to Quebecois music, stuff I’d listened to before, because when I had my sexual awakening, and discovered the queer world, which is very anglo, I enjoyed that aspect. I went into exile from my language, in a way that was fully emancipating. But now I'm returning to the source. I think there is this pleasure to being in your native language, you have a more immediate relationship to it. And I think there is something wonderful about French variety music. Like, I'd never really listened to Charles Aznavour, but the lyrics are just so great.

O: I had friends in high school in France who tried to get me into French variety music, and I was mostly, like, over it. I thought it was fun in theory, from afar. But now, I'm more interested. I don't know why...

G: You're thirty now. In your thirties?

O: Yeah. Well, I'm thirty-six.

G: I'm thirty-two now.

O: Ok. Next question. Do you romanticize either language?

G: Yeah, I do like English. I like that you can be a "warm, little slut," you know. I like the order in which adjectives follow one another.. There is this concision to the language. It's bouncy. You get tonic accents every other sound. This fascinates me, and it found its way into my writing in French. Not just because I'll switch languages mid-sentence, but also just in terms of my rhythm. I feel like I hear English when I’m writing in French. Also, for me, English can't be dissociated from social networks and the frenzy of them. Like Tik-Tok. I haven't been on it much, but I think there's a lot of English in those apps, where things scroll by, bounce off one another, and there is a lot of dopamine. There is a punchiness to English.

O: Yeah, it's quicker as a language. I was a subtitle translator for a long time, and doing so into English was a lot easier, because it's more succinct. French takes more time.

G: I think that helps explain why I'm coming back to French in my thirties. There's something very sensitive about French, to do with length and softness. My writing in my twenties wasn't really related to those things, it was more frantic, more about self-expulsion. I think I responded well to English.

O: Yeah... Maybe because there is this internationality to English, for the queer community, say, where you feel like you can reinvent yourself into it and rediscover yourself in it, maybe it seems more familiar at first, but in the long run, you start to think there's something a bit cold or alienating about it.

G: I have often thought to myself that I learned to write through Grindr. Because with speed dating you have to seduce the other person, show them you're witty, and I loved that. I love the textual flirting that comes before an encounter. I can spend hours texting someone, bouncing off one message after another, it excites me.

O:Sometimes with contemporary French lit, I can feel a bit bored, and with your stuff I don't feel that at all.

G: I think when you're on social networks a lot, you internalize the language of addiction pretty quickly. You know you're looking for a fix when you're on them. And I think in a lot of my writing, I'm really looking for a high.

O: You think you're after a dopamine hit in writing?

G: Yeah. I think I realized that a few years ago after writing my first books. I look at them now and I see that I was chasing after that high. Notes from the Underground is all about going out, doing drugs, pleasure, jouissance. But I also want to say that writing can be like edging. I've written some very short books, yet it takes me four years to write them. I feel like that says something about my edging abilities, since they were pretty succinct. But I think this relates to something else I've been learning, lately, which is a slower, more sensual approach to sexuality.

O: Yeah, I think that's getting older, too. So, you studied film, and then?

G: Literature, then medieval literature. In English and French. I was really fascinated by medieval literature, because of its poetic and also allegorical aspects, I realize now. They're works in which one thing can mean a thousand. There is a surplus of meaning in medieval works that draws you into the work, makes you project your own feelings and fears onto it, and I liked that.

O: There's something very mysterious and inaccessible-seeming about medieval literature.

G: Yeah, well it's the dark ages. I've always seen myself as a misfit, and when you put yourself in that category, you're attracted to the fringes. I think I sort of figured, this is a period no one likes, but I'm going to be able to love it. I'd known I had wanted to be a writer since childhood, it was a dream of mine. And in university, it was taboo, where I was, to say you wanted to become a writer. We all studied literature, but we couldn't say we wanted to be writers. At some point, I thought, fuck that, I'm going to live my life. So, I started talking about that with people, and organizing writing circles with friends. And we let ourselves get taken up in that momentum. You have to do things that nourish you and give you life.

O: Yeah, you have to follow your jouissance instincts, at least a bit, do things that give you pleasure.

G: We're back to jouissance.

O: It feels very francophone of us, to be talking about jouissance so much. What would we even say in English? Just "pleasure"? Anyway, I feel like you have a pretty big community of francophone, maybe queer writers there now?

G: Yeah, there's been a real boom of queer literature in Quebec, lately.

O: How did you find Triptyque, your publishing house?

G: I was really spoiled. I was doing these writing circles, and I wound up realizing that what really worked for me was first-person writing, that it caught my friends' attention more, made them react. And then I went to Berlin, and I would post these recaps of my nights out on a fake Instagram account in private for my close friends. And my friends were really into them. It was the first time my writing had garnered so much enthusiasm. It really struck a nerve. So I figured I'd create an instagram to post these notes I'd sent to my friends. I was planning to post sixteen of these stories, and as soon as I'd posted the second one, a publisher contacted me telling me they wanted to publish my stories. I was really self-doubting, I was like, no, I shouldn't... But they insisted it'd be interesting. And I said well you know there are sixteen stories, maybe you should read them all before making me sign a contract... so they said ok, sure. So he read the sixteen and said, these are great, but we need a bit more. So I wound up writing thirty three. And then the same sort of thing happened for the English text. The first day an article came out in the press about the book, a publisher wrote to me telling me he wanted to buy the rights in English.

O: So it was through social media that you re-entered literature. Was it an obvious choice to write the book in French?

G: Yes, but not immediately. It had to do with translating what I had experienced for others. I wanted to translate feelings initially beyond words into something my francophone friends could read. So, I think it was about translation to begin with.

O: In your second book, you do still have some English in there, you'll use English words like "weird" or say your friends find you "delusional" wanting to photograph the skate park. Why those choices? Do the English words just speak to you more?

G: Sometimes I switch to English just to emphasize something, or because it's easier or more economical to say it that way. Sometimes it provides ironic distance. It de-dramatizes, it makes it funnier but also offsets it. And the Straight Park, compared to my first book which was really diaristic, is more about reflecting my environment, which was really anglophone. I think what's most English in that book is the dialogue, which is what my reality is like, my friends are often more Anglo than Franco. I'm happy you asked me to talk about writing between languages. Even if I'm closer to French in my writing, Frenglish is still important to me, in a way that's aesthetic and political. In Quebec, I was raised in a household where English people, politically, were the enemy. The other. And in the media you still have this fear of English being instrumentalized. Governments and politicians will use it like a scarecrow, to say "this is what will happen if we don't put in more drastic measures." But in my daily life, I don't see that. I'm drawn to English-speaking people, I want to overcome the barrier that's been placed between us, and I feel our bonds are strengthening. There's a disconnect between what's said in the media and comments online, and with the youth, because we were immersed very early on in English. I think it was more natural for us, so I don't know if it'll become sort of an artifact, this English/French discrepancy, for the next generation. Often we're told, if Francophones just let things go with the flow, French will disappear. But I really don't feel like that's what's happening. Even if there are more connections between the languages, even if I punctuate my sentences with English. I don't think that leads to the disappearance of French.

O: I think your writing looks like a realistic preservation of what "francophoneity" can be.

G: There's a Quebecois writer named André Belleau who says languages are a bit like hoes, they like to go frolicking about and screwing around all over, and to bring words back. And that's really my experience. I was a hoe for English. But you bring it back into French and it only strengthens it. As a medieval specialist, the first texts that fascinated me are in Anglo-Norman, which was the Frenglish of the time. English comes out of Anglo-Norman, which is French, or Frenglish. That cultural intermingling has always happened, and it hasn't ever killed a language.

O: Yeah, it's true there is a very old linguistic interrelation there. Did the skaters in the Straight Park speak mostly English?

G: No, mostly French. But the queers who would go there were more anglophone.

O: Ok. Maybe because there are just less of them? They find each other in English because they are a minority?

G: Yeah, and because it's the international language. If you actually counted it, there might be as many French as English speakers, but this is one of the features of spoken language in Montreal; francophones are very welcoming, really, as soon as they feel there is any kind of struggle, they'll switch to English, even to the great dismay of people who are trying to practice their French. And we have this other thing, as francophones, of wanting to help people, and of wanting to practice our English.

O: So, you use Frenglish, like you have a character who says, 'what do you get out of doing drugs' and you say 'I probably 'get' nothing out of using drugs' ['get' in English in the text]. And later you're hungover and you describe something as Incrédible. It’s funny when your brain is no longer able to situate itself between languages.

G: Yeah, you get lost between languages.

O: I wonder sometimes whether this hesitancy between languages doesn't lead to a hesitancy with everything; for instance what you call your “legendary struggle to say no when someone uses the imperative” on you. I often feel pulled in two directions in this way, too, I don't know if it's about queerness or linguistic in-betweenness or something else, but this sort of inability not to 'go with the flow,' this sort of existential indecisiveness that, in wanting to be chameleonic, creates a state that I think ends up defining me, and that leads me to responding in the affirmative to things, in a kind of out of body experience way. Sometimes I wonder if this state of passivity in life, this kind of witnessing of things, is in a way part of the writer's condition, but it's also kind of a condition of interlinguistic living, I don't know.

G: Yes, I really agree with that, I feel it too, sometimes. Thinking there is a kind of gap within yourself; you have to find your words, make choices all the time. I think the Straight Park is a book where I try to move from a passive to an active role. But I think Frenglish has this huge creative potential. You're using this totally new envelope, which creates a playing field you can appropriate.

O: You can affirm yourself in a certain way.

G: Yeah, it's like this generational speaking up. I'm not saying I represent a generation. But it's the consequence of the conditions I grew up in. We should think about that more. It makes me think of the expression 'lost in translation,' which is a way I often feel, between cultures, languages, and also between a moral and totally liberated stance, like I want to be focused on pleasure and jouissance, but at the same time, I don't know, I fall back into this moral stance, I even get a bit lost in it.

O: Yeah, you're often torn between this limitless progressive momentum versus this need for strictness or moral rigor. This reminds me of something else you said, where you feel like when you choose to talk in one language or another, you get this feeling of witnessing yourself. And maybe this is also related to this sense of being torn between discipline and liberation. At some point in the book you say you meditate, you talk about telling yourself you're a smooth lake when photographing someone, in order to stay steady. In meditation, you often have this thing of watching yourself, and of therefore thinking that you are supposedly something other than yourself.

G: Yeah, I'm really into that right now. I've been trying to incorporate this idea, you know how they often say that in Western culture we think of ourselves as individuals, but when you start writing I think you realize how connected we are to others. We can't live independently of others, even if we'd like to sometimes. We're always caught up in this web of complex relationships. And I've been trying to incorporate this idea, lately, that I am not myself, but another. But it still kind of escapes me. When meditating I get caught up in my thoughts again. I also really seek out sensory experiences; I'll sit down to meditate and be like, "Ok, I'm ready to have my transcendental experience!"

O: Ha, yeah, like "Let's go!" Tik-Tok style.

G: This probably isn't good for marketing, but part of the Straight Park was a kind of outburst against this pressure to be happy. In Quebec media, there is this thing people keep saying, that you should write without pathos, not express unrestrained pain. And I think gay people in particular experience that pressure, because they are told – or were, I think the discourse is changing – that everything had been solved, that things were better now, that we had gained ground.

O: This "it gets better" stuff.

G: Yeah. But looking around me, especially during the pandemic, I found my friends had a lot of mental health problems, we were all very anxious, there was a lot of depression in the community, though that wasn't just true of gay people. But I felt like this pressure to be happy totally silenced the real psychic pain I saw around me. I think in the Straight Park, there was this will to be like, yes, sure, it does actually get better, but you have to go through a rite of passage, face your psychic pain. There is something you have to confront, incorporate, and accept. We'll always live in a straight world, and that's going to create a few wounds. You have to transform those wounds into creative potential, but you can’t create without facing them.

O: You have a sentence I really liked that says, "The racket of demonstrations calms me." What kind of protests are you talking about?

G: We had a lot of demonstrations around access to higher education in 2012. Students took to the streets, and it started a big popular movement. People started supporting the students a lot, by going into the streets but also by banging pots and pans every night around 7 or 8 pm. It was really a huge movement in Quebec. And yeah, having that racket calms me, you know I mentioned I grew up in a slightly underprivileged area, and we were near the highway, and I'd tell my dad that I found the constant noise from the cars calming. It's like the ocean. I think it quiets your internal chaos. In the Straight Park, when I say that line, it's because finally it feels like what's going on outside matches what's going on inside, finally society is reacting to how I feel inside, there was something reassuring about that. In 2012, it was like this big glimmer of hope that swept the Quebecois people up, and afterwards there was a lot of nostalgia for that moment of coming together and expressing anger.

O: Yeah, it generates joy. It's hard not to be nostalgic for those moments, because these imagined communities suddenly appear, and there is this momentum and excitement that's created. I took part in a lot of demonstrations here in Paris when I was in high school, and I discovered that I felt very comfortable when I was alone in the midst of the crowd. I loved that feeling of bouncing around all over, and being kind of free within that chaos.

G: It reminds me of Berghain, I loved being in the middle of the crowd, I found it very meditative, being in those places. And as an observer, too, watching people dance, there's a pleasure in that, there's so much going on.

Great interview, and i'm very excited by this column.

This was great and it's very exciting to hear it will be a recurring column!!