DISPATCH: A Poetry Reading at Zoème, a bookstore in Marseille

On solitude, translation, and choosing bookshelves over the sea

The day began with a bolt out of bed to catch a boat to an island. It was my eighth morning of thirteen in Marseille and I’d been urged to take a day trip to the Frioul archipelago by multiple people who know the region well but me just a small amount. I was in Marseille with the ostensible and knowingly baggy ambition to finish the translation of a book and advance on the translation of another book, but my first seven days and nights had taken shape around the writing of a text that no one needed, for which I was not behind on a deadline, as well as the watching of Jean-Pierre Léaud, the sloped fact of his life, and hours-long evening naps that consequently stretched my nights to four or five in the morning. Hence the counting, hence the bolt. I’d barely slept and feared missing the boat, an activity that, I figured, or hoped, would activate my remaining days in Marseille with stable patterns of time and progress.

You’re like, where’s the bookstore? I’ll get us there fast because the islands bored me—people who know me even a medium amount would have predicted this—and after no more than fifteen minutes of walking on a gravel path in direct sunlight I wanted off. I was also stuck, because the next return boat was not expected for several hours. I sat on a bar patio and turned tenderly towards the image, unspooling before me, of a man holding a woman’s hat for her while she was in the bathroom. The sentimentality of this observation might be made tolerable if I include the detail that I’d ordered a strong beer—it was barely 11 in the morning, I was feeling rebellious, the cold drink was delicious. Then I read a couple pages from the opening of Christa Wolf’s 1968 novel, The Quest for Christa T. (translated from the German by Christopher Middleton), plucked from the bookshelves of the apartment in which I was staying. By the time I returned it was mid-afternoon and I was tipsy and sunstruck. I fell asleep for a few hours after watching twenty minutes of The Mother and The Whore, and as I drifted off, I wondered, as was my habit in Marseille, what I was doing in Marseille, what others would do in my place in Marseille, what one comes to Marseille to do.

One thing I knew I’d do was attend a reading at a bookstore later that night, the poster of which I’d been forwarded by a friend in Toronto—where I live and work as manager, bookseller, and programmer at Type Books, an independent bookstore—and it was a seven-minute walk from the apartment, though I took a slightly longer route that evening because I wanted first to stop at a vintage store, having arrived at the decision to buy a miniature metal purse I’d looked at the day before. It was the birthday of Derek McCormack, writer and friend and buyer at my bookstore and buyer, too, of all sorts of impractical objects, and I’d told him and myself that I would buy the purse in his honour. It is three by five inches and rock solid, bronze-toned metal, thinly chained, ornately clasped, and shaped like a pillow (another justification I drafted for the purchase was that I would call it privately, though I suppose this now means publicly, my pillow bag, after Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book). It fits one lighter and two cigarettes, or a few bills and coins, or one debit card and one apartment key.

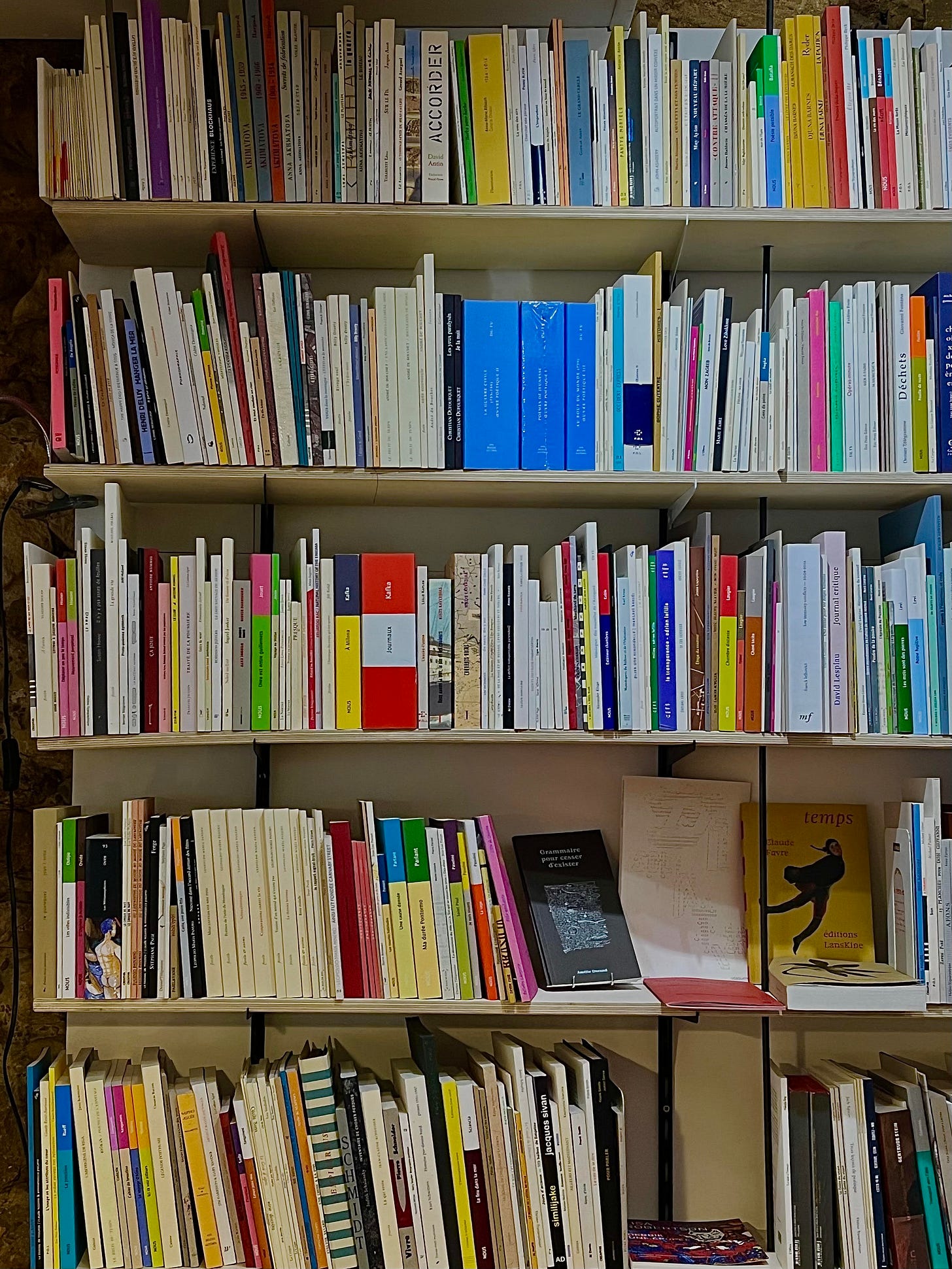

The bookstore, Zoème, is also a publishing house and gallery. I arrived thirty minutes early on purpose, unsure as always whether there would be a crowd, but no one else was there: the store was empty save for about twenty chairs and a heat that assumed an almost physical presence. I had begun to browse when a woman emerged—at the end of the night I learned her name, Julie Cazard, long-haired and deep-voiced, artist and bookseller—and asked if I needed help finding anything, using immediately the informal address in French, which thrilled me: I prefer the tu because I have more experience conjugating with friends than strangers or so-seeming authorities. I said no, just browsing, am here for the event, etc., but then realized I didn’t want to dismiss the interaction, wanted instead to keep talking, to be in conversation with her, she who was unwittingly offering herself as my first prolonged interlocutor after more than a week spent almost entirely alone.

I continued by doing what I always try to do in a bookstore and which always feels unaccountably lame: I told her that I, too, am a bookseller, and after being asked to repeat the name of my bookstore, turned to the side to demonstrate the tote bag I’d brought to France in the spirit of international promotion! A brief aside: this had at the beginning come to me as an industrious idea but I’d already begun to resent it—people in Marseille kept entering conversation with me in English after seeing the bag, well before they had an opportunity to hear my French and, I’m told, subtle accent. The repetition of this interaction felt weird, borderline provincial, since I know there to be loads of French people who carry tote bags with English text on them, and this didn’t happen to me in Paris. Bref: Julie indulged me and made moves I recognized—handing me book after book after book, it took no time at all for her to build for me a pile, each spine chosen individually but in quick succession, many of which, she emphasized, were published by the bookstore’s publishing imprint, including the French translation of Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters and a book written by Grégoire Sourice, poet and writer, as well as her colleague, a bookseller and editor at Zoème. “Because he wouldn’t do it himself,” she said, and I nodded, said I knew this part by heart.

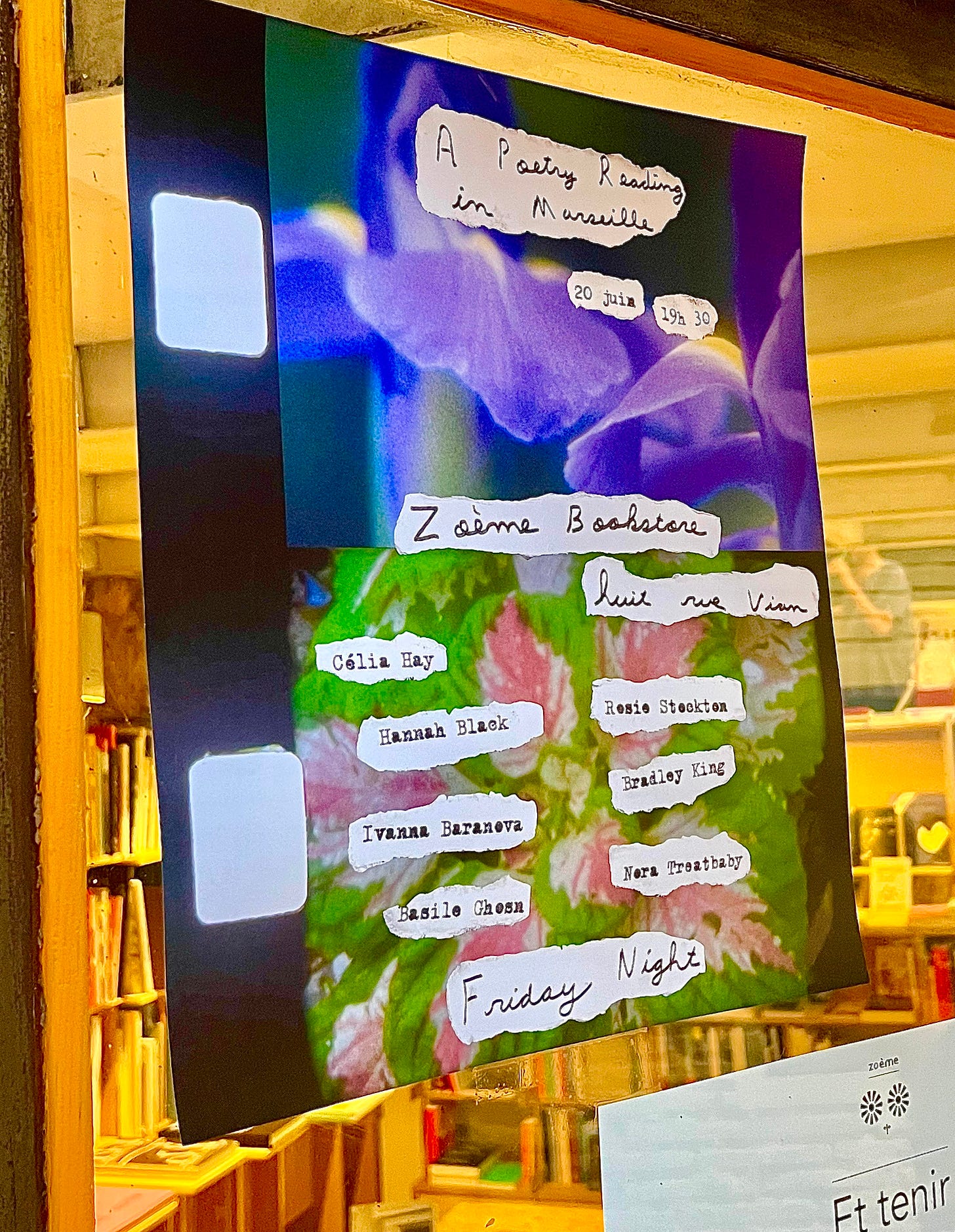

Grégoire then appeared at the doorway, half-inside half-outside, still smoking a cigarette. He saw me holding the French edition of Iman Mersal’s Motherhood and Its Ghosts, translated from the Arabic by Richard Jacquemond, which Zoème also published, and told me it was excellent, at which point I introduced myself, said I know—I’ve read it, sold many copies of its English sibling (trans. Robin Moger, published by Transit Books) at Type—and also hello I am holding your book. A few minutes later the first reader arrived: Bradley King, explaining fast and in English he’d come early to help set up the space but everything, he saw, was already prepared and he was grateful. I followed Bradley and Julie outside, passing a poster on the door that listed all the readers: Célia Hay, Hannah Black, Ivanna Baranova, Basile Ghosn, Bradley King, Nora Treatbaby, and Rosie Stockton, whose new collection of poems, Fuel, published by Nightboat, was being fêted that evening, though she only had two copies for the bookstore to sell. This detail gave me a rush of respect for Zoème: the function of this event was not to sell books, but open a space and choreograph a coming-together, however sweltering.

One by two by three the readers arrived and because I had arrived early and alone, I was integrated with ease and accident into a sort of bookstore welcome brigade, introduced to everyone as if my presence were by design and not desperation. Everyone smoking cigarettes was smoking cigarettes they laboriously rolled themselves, which seemed to me an annoying feat of patience and then I remembered these were poets. I was wearing the new purse and received compliments and questions about its provenance for the rest of the night.

I was privy to dialogue usually reserved for, at least at my bookstore, the basement—the hushed conversation before an event about proper pronunciation amongst the readers, each of whom was asked to introduce the person after them. Everyone knew everyone already, but this moment still had to happen, and Basile, with pleasant neutrality and possessing the surname that incited the most anxiety (for Bradley, his very good friend, especially), said something like: “we’re learning how to say the last names of our best friends.”

At 8 o’ clock no one had arrived other than the readers, the booksellers, me, and maybe two other people. I learned then—my events coordinator hat feeling at that point a bit tight—that it was universal, the occasional failure of good, even big-name, events to attract audiences they deserved. On sait jamais was repeated, we wait was repeated, c’est pareil pour nous à Type I assured. But then more and more people showed up and ultimately all seats and two benches were filled and the bookstore remained too hot.

I sat in the second row. Once the reading began I felt delivered, at last at a book event—precisely the work I was supposedly on vacation from but also precisely the work to which I wanted to return, and now that I had all was good, I was relaxed. I was sitting near the French translation of Kafka’s diaries, to which my attention had been directed not for the title but for the look: the French edition resembles the Dalkey Archive Essentials series, its thick spine most closely resembling that of Miss MacIntosh, My Darling by Marguerite Young. An open window upstairs let in some air but also live street music, to such an increasingly disruptive degree that a wink exchanged between Julie and Grégoire tasked Basile with the mission, during one of the readings, to ascend some impossibly creaky stairs and shut it.

In the anti-tradition of poetry readings throughout global history, not a single reader went over time. Everyone was sweating and everyone respected the clock. Bradley read from a new magazine he’d just put together; Basile read poems he’d handwritten in pink ink; Ivanna read from a chapbook called Threshold and some recent work; Hannah read from her novella Tuesday Or September Or The End that everyone loved and wanted to buy but is now out of print, wearing a baggy black t-shirt that read: “FROM THE RIVER TO THE SEA PALESTINE WILL BE FREE / FROM THE SEA TO THE RIVER PALESTINE WILL BE FREE FOREVER.”; Nora Treatbaby read a poem called “Rent” that had the room in gasps and stitches; Rosie read from Fuel; Célia read poems she wrote in French and others she wrote in English. The only note I took during the event was a reminder to ask whether Célia had arrived naturally at the word “furrow” in English or whether she’d self-translated it from French. I wanted to know because one of the books I’d come to Marseille to translate but wasn’t translating is called The Furrow. She later confirmed that this was one of the rare words from the English poems that came to her only in French, so she’d translated it into English. A poster that hung behind each of the readers depicted the title of a book on the Guinean revolution by Amilcar Cabral: “OUR PEOPLE ARE OUR MOUNTAINS.”

The day had begun with my going to the sea because that is what, I grasped, people come to do in Marseille: they enter the busy city in order to leave it and go to the sea. At the sea earlier that day I transcribed into a notebook the following passage from The Quest for Christa T: “The ingenuous open heart preserves one’s ability to say ‘I’ to a stranger, until a moment when this strange ‘I’ returns and enters into ‘me’ again. Perhaps all our going out and coming in teaches us to repeat this moment.” The lesson I learned in Marseille was to go out and come in, to ditch the sea and move towards the center of the city—that is, after the nap, the shower, the change into the wrinkled silk dress and the purchase of a superfluous accessory—and go to Zoème, where bookshelves are my mountains.

enjoyed reading this dispatch a lot!!!!!

Ooh, that purse.