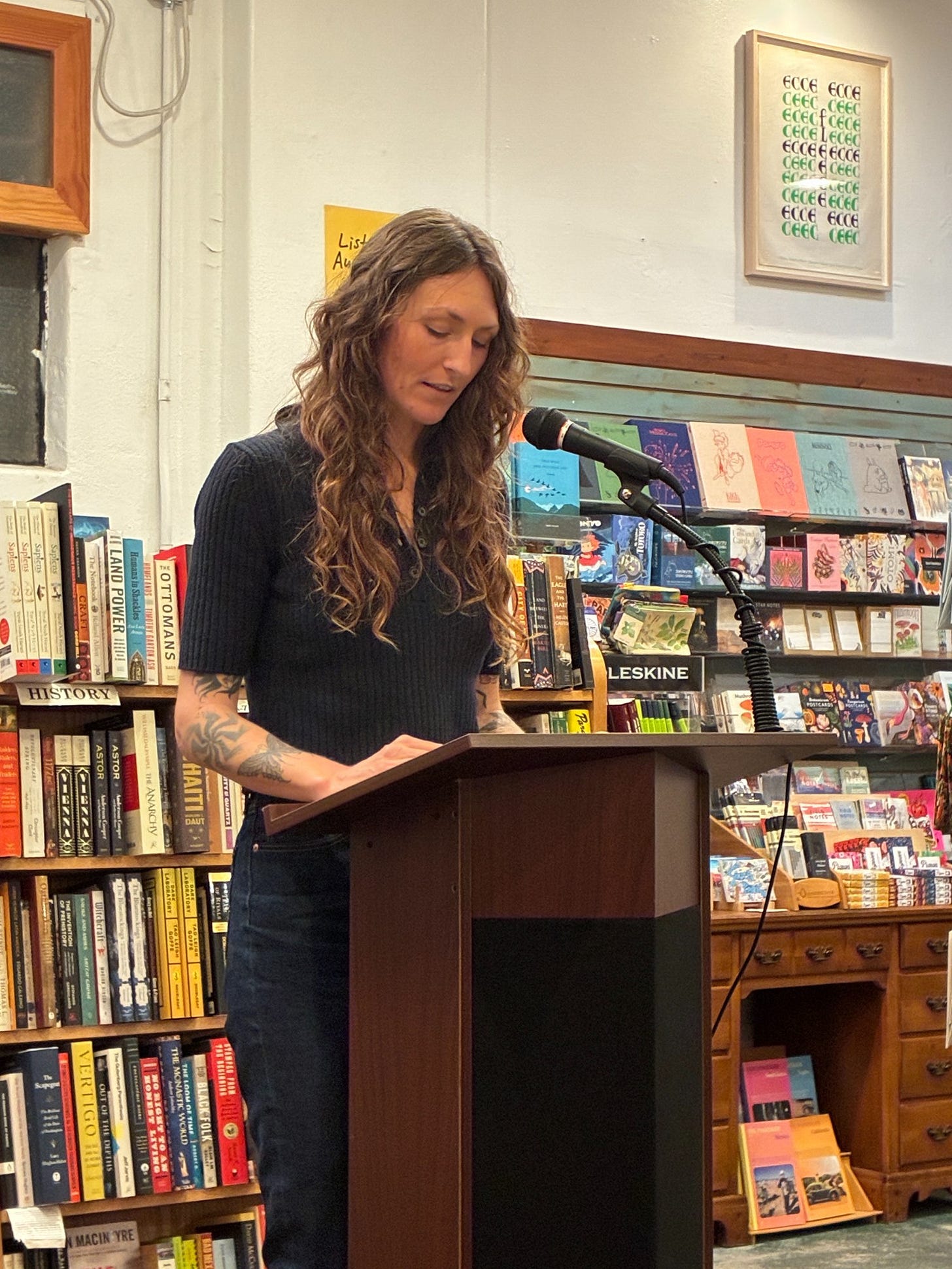

I met Shelby Hinte at the 2025 AWP Conference that was held in LA. We’ve had some fun dispatches from there published on Zona Motel, so I’ll spare you my less glamorous account (I came as a booth babe for an editing company and spent a lot of time slipping gold-foiled matches into strangers’ bags), but getting my hands on a copy of Howling Women was a highlight of that trip.

Before Howling Women, I was reading the third book of John Updike’s Rabbit tetralogy, Rabbit is Rich. Between those novels, you need a reset; they feel a bit like rolling around in mud. Howling Women wasn’t just a reset but a sharp divergence from the world I’d been in. Howling Woman, a character at the center of Hinte’s novel, reminded me with a kind of gnarled assurance that there are consequences to cruelty.

I started the novel on my second night in LA and finished it on the plane back to New York. A few weeks later, both of us on the other side of a move, Shelby and I chatted over Zoom.

Dasha Sikmashvili: Congratulations on Howling Women being officially in the world!

Shelby Hinte: Thank you so much for reading it and reaching out.

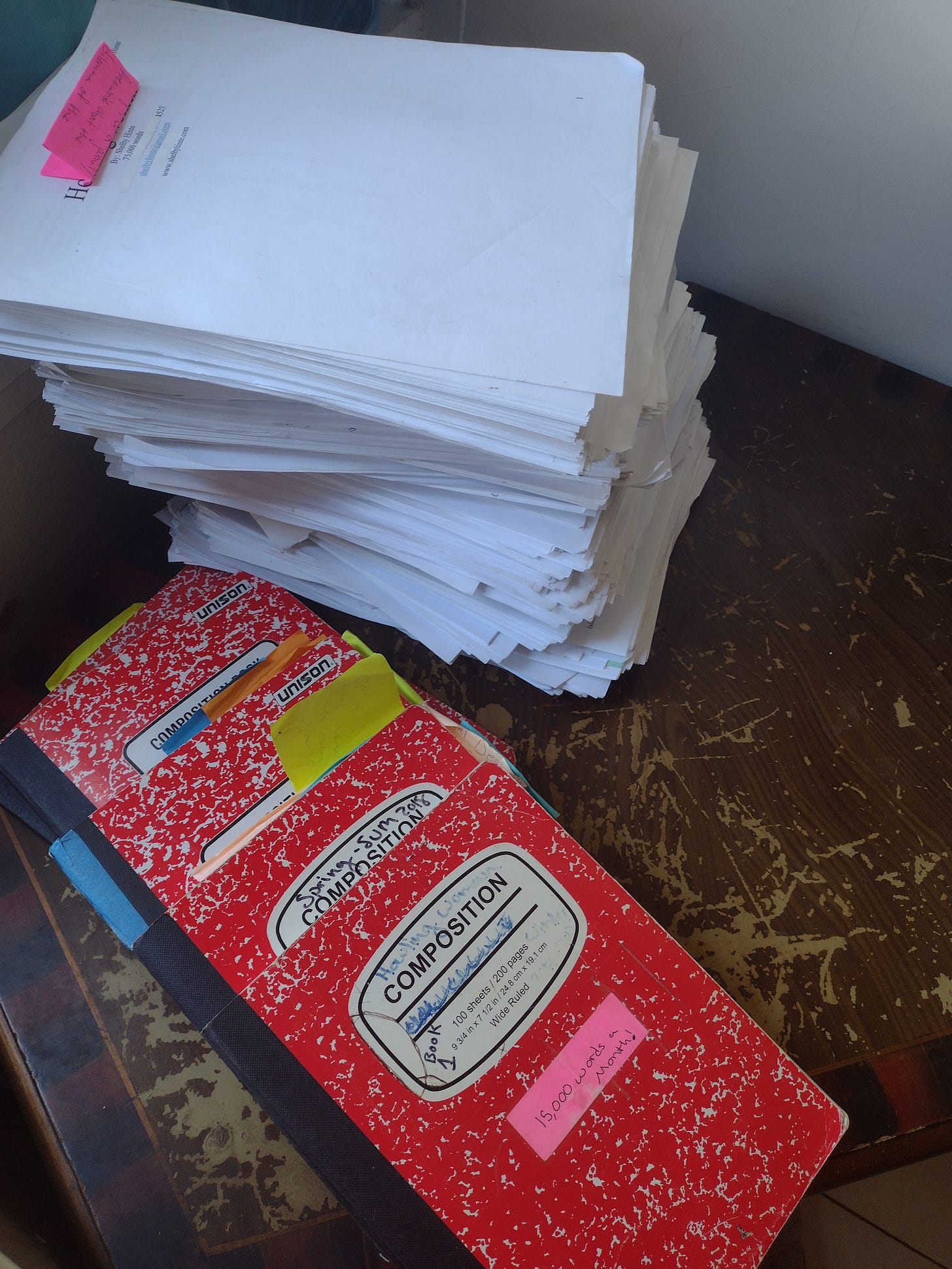

DS: When I read in the acknowledgments that this was a seven-year process, I felt really relieved. I've been working on my novel for five years. Can you talk about that seven-year journey and how the published version differs from earlier drafts?

SH: You probably know how it feels then. I wanted to be done sooner—there were times I thought I was done sooner. I've written other books before Howling Women, but never finished them. They were 100 or 200 psychotic, messy pages without endings.

With Howling Women, for the first time I was like, "I did it. I wrote a book all the way to the end." The first draft took just under a year. I was a high school teacher, writing every day before work or on weekends, using spring break as at-home writing retreats.

I thought it was done four years after I started. I queried and got traction—most agents requested fulls. But they were passing, and every time I got a pass, I'd see new things to fix. After six months of querying with no bites, I paused, wrote something else, then came back to it.

Year five was when I did major overhauls after that big break. I felt like a different person and writer. I'm so grateful it didn't come out when I was impatiently ready. The greatest gift was that people passed on it because it wasn't the book it is now. It's wildly different from the first iterations.

DS: When you came back after that gap, did it feel like "Who was this person who wrote this book?"

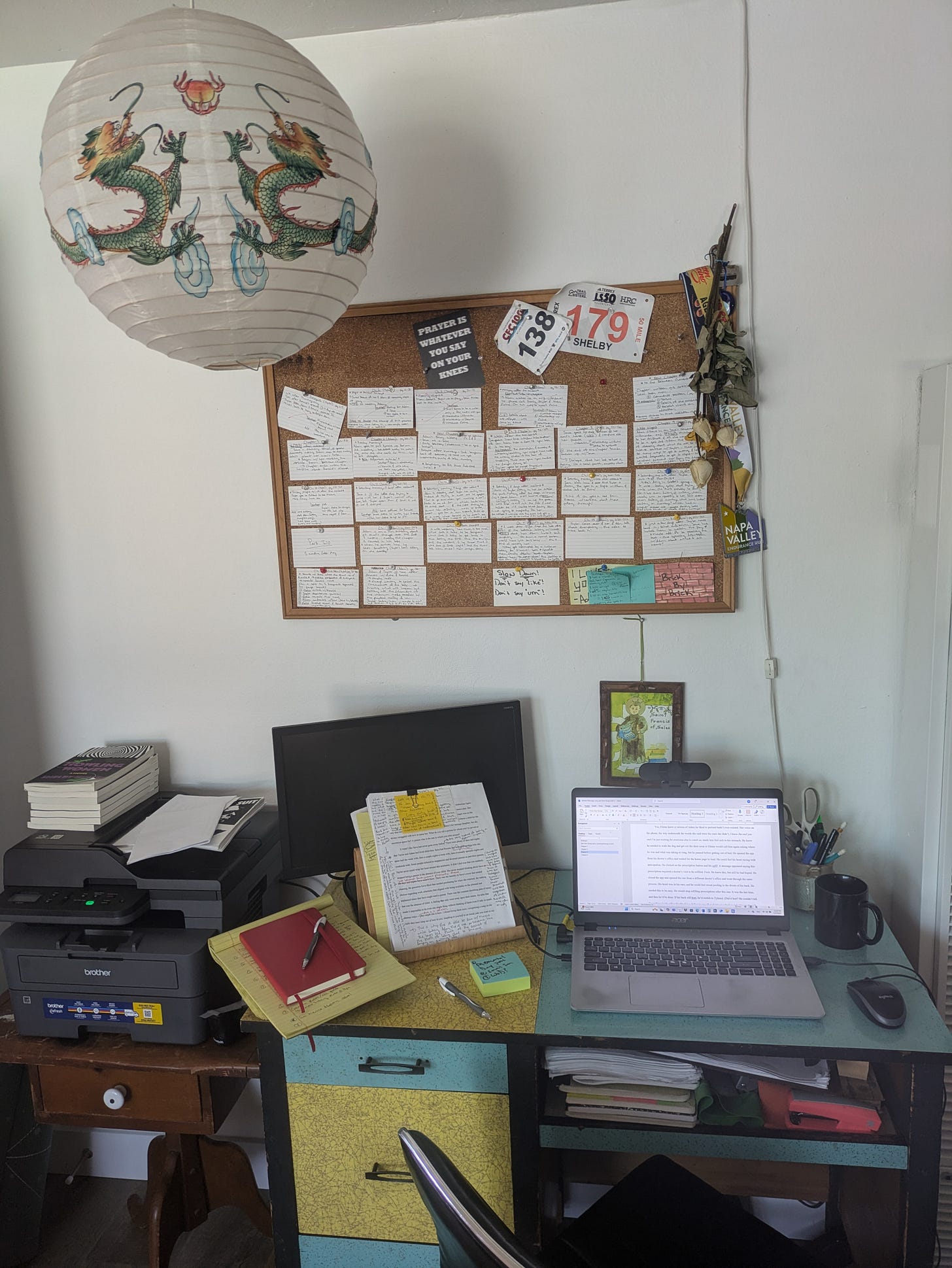

SH: Absolutely. When I came back, writing was easier and fun. I saw problems and had creative solutions I didn't have before. I learned that a huge reason to publish a book is simply to stop rewriting it—I probably would rewrite it forever.

When I sent it to Patrick at LEFTOVER Books after a big revision, I felt like I'd made something different. He responded within 24 hours, wanting to publish it. He talked about what he saw the book in conversation with, which gave me permission to do a rewrite I wasn't brave enough to do before. There was suddenly this fear of "Oh shit, people are going to read this now."

DS: Can you talk about the indie publishing experience versus the traditional route?

SH: My biggest hurdle with agents was feedback of "I love this" followed by "but." They'd say "It's wholly original" or "The voice is so unique," but that felt like a problem because then came "but I don't know how to launch an author with this as their first book." Many suggested sending my next book instead.

At a certain point, I realized I predominantly read indie presses. Why was I trying to go down this route when this isn't even the books I read? With Patrick at LEFTOVER Books, it was wonderful. He only wanted to make the book more of itself, not something else. One agent had said, "I can see you're actively avoiding doing X, but if you do X and change the ending to Y, I could sell this book." I said, "Yes, I am actively trying to avoid that." That was never a conversation with Patrick.

DS: I love how you pulled elements from crime and noir while staying literary. Are you a big crime reader?

SH: I don't read many crime books, but I used to have a long commute and only listened to audiobook thrillers—mostly domestic thrillers. It's also a genre of television and film I watch a lot. When I was trying to create stronger pacing and distill the book down—it was twice this length in early drafts, 130-140,000 words, now it's around 70,000—I realized I love how thrillers use the narrator breaking the fourth wall. Whether they're on trial or in an interrogation room explaining themselves, then drifting into flashback. Having listened to something like 100 thrillers, that structure was ingrained in my brain.

I also really admire some Latin American writers who break that fourth wall, where you think you are in this third person narrative and then you pan out a bit further only to discover you are in a singular narrator’s story and it feels as if they’re talking directly to you. My interest, as far as genre, was more about structure than plot.

DS: You created an entirely fictionalized setting with the town of Yu. Why not use a real place?

SH: I do this in both books I've written. When I feel insecure about it, I think, "It's a book. I made it up. Everything else is made up. Why can't the town also be made up?"

Part of it's not wanting to research every detail of a specific place and still get it wrong. But mainly, these made-up towns serve to create something fictional. When characters and plot are made up, I have a hard time thinking any specific real city exists in their fictional space.

What I'm going for is the feeling of a place rather than geographical accuracy. You can only create that if you create something that doesn't exist in anyone else's imagination. People can bring their own associations of the Southwest or California.

DS: Here’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot as I read Howling Women. There are many references to mysticism and spirituality in the book. What's your relationship to those themes? Are they big in your personal life?

SH: I've had a fraught relationship with religion and spirituality. I grew up really religious—single mom, church babysitters, missions in Mexico, Christian school. Then terrible things happened and I thought, "How can there be a god?" In college, god was uncool. I was anti-religion for years.

More recently, I have a prayer and meditation practice, but it doesn't feel tied to religion. It's a breaking from the highly intellectual life I thought I wanted. I was in academic circles where science or intellect can answer everything. The more I was in those spaces, the more arrogant it seemed to think any one school of thought could provide all answers.

Where I've arrived is at a place of constant questioning. Isn't it arrogant to think we're large enough to know everything? There has to be something unexplainable. I don't have to name it, but there are things that feel fated.

My mom was an ICU nurse who specialized in end-of-life care at the end of her bedside career. She says, "I believe in something bigger because there are people who should live—everything scientifically says they should—and they die. Then someone who should die doesn't." Science may have answers to explain moments like this someday, but right now it doesn't.

DS: Female relationships dominate this book. What was your relationship with female friendships growing up?

SH: For a lot of my younger life, I had really intense relationships with women where we'd be obsessed with each other—kind of unhealthily. There was also competition I felt with other women that was bred into me. By my mid-twenties, when I began writing, I didn't have many female friends. I was desperate for close female friendships. Now all my friends are women. The bonds I have with them are the deepest I have with anyone.

When I went through a big life transition recently, it was women who got me through months of emotional turmoil, who showed up to help me move, who saved my life. I think this book was my way of writing female friends into my life, which has been the most life-saving experience.

DS: What's next for you?

SH: I don't know exactly, but I'm open to whatever the universe provides. I've been working on another novel for four years—every time I put Howling Women down, I'd write a full draft of this other book. I think this will be the fourth draft.

My life has been chaotic since December, so I've mostly been journaling and turning some material into essays. What I'd really love is to get this rewrite done because I'm in an interesting position. I stopped rewriting before because what was happening in my life became too similar to what happened in the book—I felt too emotionally torn up to write that story.

Now I think I could do a rewrite from this vantage point. I'd like to channel this strange position I'm in and get it done quickly, because I don't think the version of me now will exist for very long. I want the version of me that exists now to rewrite that book, because if I wait too long, it will become something different.

Thanks to Shelby and Kristen! 🐺

the cover of the book is one of the coolest i've seen in a long time