INTERVIEW: Taylor Lewandowski and Lynne Tillman by Juliet Escoria about THE MYSTERY OF PERCEPTION (Archway Editions)

The ordinary versus the extraordinary. The fleetingness of time and memory. Publishing on independent presses. The ridiculousness of identity.

In 2010-12, I was a graduate student and I went to readings all the time because I was writing this events coverage column for Electric Literature. I met all sorts of writers: Mary Gaitskill, Colson Whitehead, Jennifer Egan, Don DeLillo. I learned that writers are not the most socially gracious people, although there are exceptions, and most notably, for me, was Lynne Tillman. I ran into her frequently, as both a reader and a member of an audience. She stood out not just for her writing but also as a person: an excellent conversationalist, a person who knew a lot of things about a lot of things, and somebody who actually listened attentively—even to me, a nobody student.

These qualities help make her writing so affecting. Throughout her books, Tillman shows herself to be a person who is interested in the world, interested in what makes us, as a species, “tick.” Her writing is meticulous in its attention to detail and ability to parse complicated things like identity and morality, and always driven by spirit, artistic integrity, and generosity.

Archway Editions has now published a book-length interview, The Mystery of Perception, by Taylor Lewandowski with Tillman that covers much of this: Tillman’s four decades of work, her approach to art and publishing, her interest in people and this strange thing we call “identity.” Lewandowski, a high school teacher, bookstore owner, and writer, shares a kinship with Tillman, in that he too has a genuine interest in others, making him an ideal person to engage with Tillman. Their book feels both like an interview and like a refined piece of art, something I read compulsively.

We decided to do an interview about an interview, talking over a Zoom call, during which I experienced multiple technical difficulties. The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Juliet Escoria: How did this book come to be?

Taylor Lewendowski: The book started in 2022, April Fool's weekend. I was doing a reading with Lynne at KGB bar, with Stephanie La Cava, Gideon Jacobs, and Em Brill, and that was the first time I met Lynne. Before that, I had the idea of wanting to do an interview with Lynne, and I had the dream of it being one of the Paris Review interviews. That was the original framework.

I met Lynne, and I thought we had a really good rapport after the reading, and then the Paris Review thing didn't work out. I conceptualized the interview as an opportunity to read her oeuvre and hopefully piece together all of the many scenes and lives she's so far lived. I read through some of Sylvère Lotringer's early Semiotext(e) interview books, especially David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years on the Lower East Side.

JE: Lynne, how did you feel about this idea of an interview that's book-length? Was that something you were immediately into, or was it something that you had to negotiate with yourself?

Lynne Tillman: I didn't expect it to happen. Because Taylor and I had an interesting conversation after we'd done this reading, I thought, Sure. I've been interviewed over the years, and I didn't think it was going to be any different. When he talked about the length, I didn't think it would ever get published, and I wouldn't be revealed—which is what I don't want to be, really— and as it became more of a reality, I became much more anxious about it.

As Taylor knows, I didn't want it to feel gossipy. Taylor and I engaged about that. I think that is important about it— we had differences of opinion about things like the self, and we discussed that, and he wanted me to talk about people. I had some reservations about that, so I primarily talked about dead people who were, and still are, important to me. When Taylor said Archway was going to publish it, I thought, Oh god.

JE: An interview is unusual too, because if you're answering questions, you're thinking more about what you're saying, and if you're asking questions, it's a very intentional listening. So was that what you were doing, or did it ever break into a regular conversation?

TL: I prepared by reading her books and anything about Lynne then I started with about twenty questions, but I'd go into each interview and sort of set the questions aside—let the conversation organically flow. Each session I transcribed, edited, and rethought where I'd start for the next session until we reached an agreed upon end. After that, we worked on a shared Google Doc, structuring it, fixing errors, etc. I hope it retains a narrative propulsion.

LT: I took things out. A couple of things that Taylor didn't want me to take out.

I've done interviews that I turned into books—The Velvet Years: Warhol’s Factory, and Bookstore—and what I did was have conversations with people, and then drop myself out of it, so it seemed they were just talking, and I didn't keep in the gossipy things. The thing about gossip is how terribly temporary it is. It doesn't mean anything in the end. Everything is temporary, life is temporary, etc., etc., so I wanted to avoid that.

JE: A conversation is fleeting, right? And you guys wanted to make something that would last, and was not stuck in time.

LT: I have a question for you, Juliet. What have you taken from it? Why do you like it?

JE: It felt like an interview, but it also felt like something different, and it helped me understand your body of work in a new way, in maybe a concrete way. It also made me read Haunted Houses. So I think that's good too— being able to pull some books that maybe people wouldn't have read otherwise. Because you have a lot of books.

LT: A lot of books no one’s read.

JE: (laughing uncomfortably) Well, I really love Haunted Houses. That book is incredible, and I'm glad simply for that.

LT: I worked on [Haunted Houses] for seven years. I thought it would be clear to people that it was dealing with girls’ lives in such a different way. And there were a couple of reviews, including a very brief review in the New York Times Book Review where it was called “sad.” “Those were sad girls.” And I was just so upset. Why use that word?

JE: Yeah, they were girls.

LT: They were girls. They were thinking about life, they were living.

JE: I sent a couple questions in advance, because if it were me, I would need to sit there and think about it a little bit. One thing that was discussed in the book is an appreciation for other people's experiences that would typically be framed as “ordinary.” But as Lynne puts it, they are actually “extraordinary lives.” I think it’s a gift in general—to be able to see the extraordinary where other people might see ordinary— and it’s an especially big gift for writers. I wanted to know about a person who other people might see as ordinary, but you see as extraordinary.

LT: I think a novelist’s terrain is the so-called “ordinary,” where we're not writing about kings and queens, or famous people. The world is divided. One percent of the world is “extraordinary,” in normative terms, and the other 99% is “ordinary,” which I reject.

I'm thinking about Richie, who was the mail carrier for our block for a long time, and the way he talked about life, and the way he talked about his child and the importance of having a child, was, to me, extraordinary. He was a mail carrier, which would be considered just an ordinary job.

And then there was a guy whom I wrote about in No Lease on Life, who unfortunately was also called Richie. [This Richie] was living on the street, and I talked with him because I was very intrigued by someone who, he said to me, did that voluntarily. He didn't want the trouble of having to pay rent. He chose our block to live on, and because of that, a group of guys who were in a couple of bands had a basement apartment, and they took him in. He could sleep there whenever he wanted. And so there are these so-called “ordinary guys.” No one knows who they are, and they're caring for a man who didn't want to have a place to live, who did not want to pay rent, or have a regular job. These are so-called ordinary people I came to know, and I put one of them in a novel, because to me, he was exceptional in a lot of ways.

JE: Taylor, what about you?

TL: I was thinking about this a lot. I'm not sure why, but the first example of ordinary as extraordinary is this instance I experienced when I visited the funeral for Pastor Murray—this grandfatherly figure in my life growing up. My dad was a youth pastor and they ran this church in Greencastle, Indiana. Pastor Murray had this social intelligence that really stuck with me. He cared about his congregation, people in general. I couldn't understand how he was always on. His funeral was standing-room only, and it was this moment where I put my disagreements aside, and reflected on this person who had a fundamental influence on so many people in a very ordinary way.

LT: Taylor, you mentioning that reminds me of the importance of teachers, like Mrs. Block, who was my first-grade teacher and my eighth-grade teacher. In the eighth grade, I wrote a story, and she recognized it as unusual or well written. It was very important to me.

I guess we'd really have to understand better what we mean by ordinary—other than not publicly known.

JE: If we need to better understand what “ordinary” means, how would you both categorize “extraordinary”?

LT: People who live a principled life, people who care about other people in whatever work they're doing—not just kindness, not just generosity. A person who thinks about certain actions. I wrote in Haunted Houses years ago, “If you have principles, you don't have to think.” When I say “principled,” it doesn't mean reacting in the same way, in a kneejerk way.

The other thing that is extraordinary is being able to say, “I'm sorry.” I've noticed how hard it is for people to say, “I was wrong."

JE: I think that's a good definition. I think of people who reach out to the world in the way that seems appropriate in the situation, rather than sticking to a set moral code that came from some religious text, or some sort of idea about society.

LT: Juliet, don't you think that, in some way, we are really stuck with this idea of “the ordinary”? There have been books, I think it started with French historians, the annales, studying daily life about the so-called “ordinary life,” and in those books, unwritten history. I don't know how we can get out of this idea that people are less than what they are.

JE: Another diminishing word is “a small life,” as though not knowing people all over the globe, or whatever, makes your life “small.” I don't even know how you would define “small” versus “not small.”

TL: I'm thinking about Frederick Wiseman's documentaries. Hyperfocusing on the supposed mundane and pulling out rhythms, fragments, relationships—forcing us to slow down and observe the really extraordinary structures of humanity, and inhumanity as well. I'm always continually surprised by what I think is ordinary is, really not. It's just actually my own kind of arrogance. If I sit down with someone, they're always something extraordinary about them, even with people I'd passionately disagree with.

LT: What I can't stand in a conversation is someone who says,”What college did you go to?” as one of the first questions they ask. It's obviously a question about money and class, and less about scholarship, because the question isn't, “What did you study? What were you interested in in school?” That's a very different question. So there are all sorts of ways in which people, in a circuitous way, are trying to find out if you're just ordinary, or if you're extraordinary.

I don't know how we can change those terms, other than to think about how focus on an object changes its status. Virginia Woolf wrote a great story called “The Death of a Moth,” and it was about her just looking at a day moth, which has a 24-hour life. And the way in which she wrote about this moth and watching its death made it, of course, an extraordinary creature. And she said, “Here's this bit of life.” I can't read that story without crying. It's so moving.

JE: What you were saying about colleges makes me think that maybe our categorization of “ordinary” and “extraordinary” has something to do with class. If you're a wealthy business person or whatever, then you have an extraordinary life. And if you're a postal carrier or an elementary school teacher, then you're ordinary, right?

LT: That's right. I think there are class issues involved.

JE: I feel like that relates to another question I had. There's a lot in this book about being shaken out of your own point of view. One quote was, “The more you are aware of how others live and think, the more you might question the way you think.” I can think of why it's good to be able to do that. But why do you think it's good to be able to do that?

LT: Well, we begin thinking in a way that's not necessarily of our own making. We're taking on ideas. We're in a context. We have a family. And that's sort of what American Genius, A Comedy was about, that we take on ideas. I became a Dodgers fan, because when I was three years old, my father said he was a Dodgers fan. I hadn’t considered other teams. We love certain things because we're born into them, in a way.

When I was living in London, I had an English friend named John Michel who studied ley lines, had theories about Stonehenge. He was an unusual upper-class man. One day we were talking, I was like 25 at the time, and he said something, and I said, “Oh, I think that too. Great minds think alike.” I was hoping I was being ironic to some extent, laughing. And he said, “And small ones.” So I never said that again.

Because the truth of that is very important for me. Susan Hiller, who was an amazing artist, and I were talking—I was around the same age as when I had that conversation with John. She was somewhat older, and was encouraging me as a writer, because I was very insecure. I knew I could be a writer, but I was also bedeviled with tremendous neuroses and obstacles. We were having tea in her apartment, and she said, “At a certain time, Lynne, you have to tell everything you know.” It wasn't until years later that I felt I was free enough to start doing that. Not that what I know is the Truth, with a capital T, but more what I think, what I was thinking about, and not being afraid of what people would think of what I thought.

TL: That's one of the major concerns across [Tillman’s] work. This idea of different perspectives and the ability, or inability, to rewire our consciousness, become more aware. We separate, or not, from the origins of our upbringing, the makeup of our biology. And the act of reading is a possibility and reflection of this freedom or flexibility or opportunity to think otherwise.

JE: The other question I asked ahead of time was: Lynne, in this book, you talk about various people you've known and loved and who have died, and say, “I don't want to forget them. I want to keep them in the present.” So who's a person you want to keep in the present, in this interview?

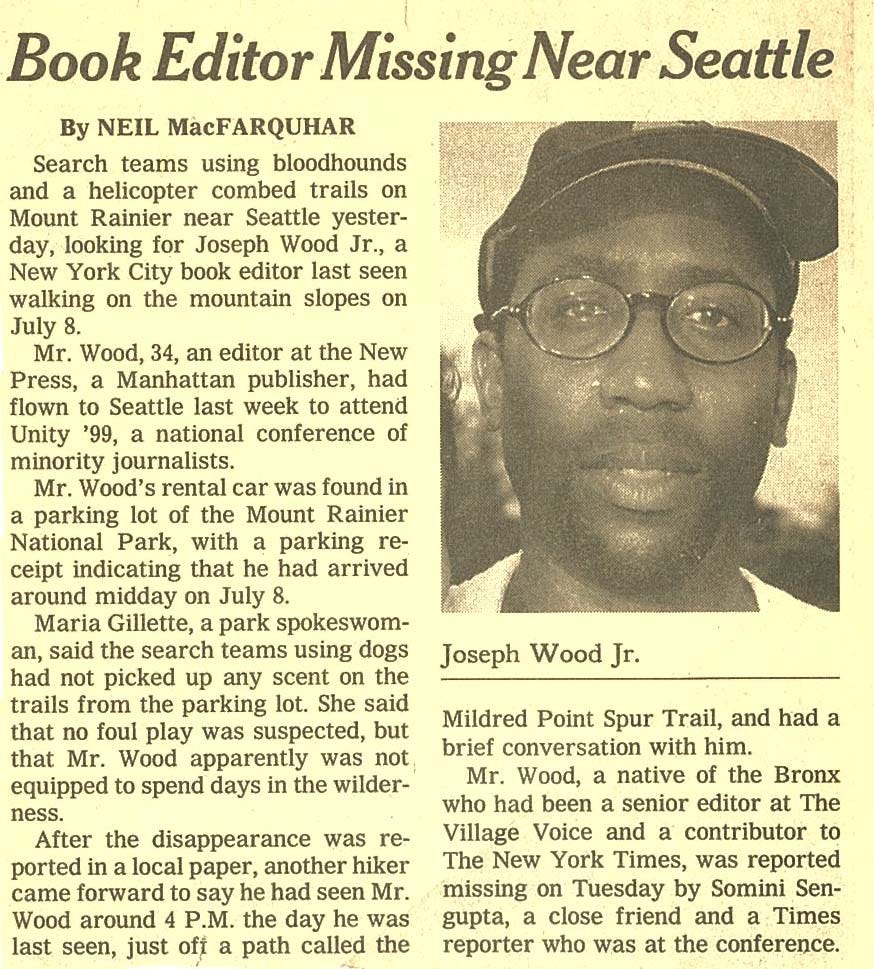

LT: I mentioned Susan Hiller, but David Rattray, I would want to keep him in the present. He certainly in my mind is in the present. Craig Owens, a great theorist who died of AIDS in 1990, and my friend Joe Wood, who died in, I think it was, 1999. He fell off a mountain. He was only 34. A writer, a thinker, a journalist. He was Black and very much involved in – not just issues pertaining to Black writers or Black artists – but cultural and political issues that also involve Black people. He was at a Black journalists’ conference in Seattle, and one day, he went up Mount Rainier. There were these [snow bridges], where the snow seemed to have something underneath but didn’t, so it’s believed he fell through one of those. For two weeks, there was a search on, and nothing was ever found, and it was devastating. I mean, death is devastating, but this was a different kind of devastation.

When I was 16, my very close friend Lois died in a car crash. I keep her in mind; she was a very important person to me. I don't want to let her go.

JE: You really did keep her alive, because that’s her in Haunted Houses, right?

LT: I did. I think writing is one way to inscribe them into a world, in a way that has a little more continuation than their lives had. I have a horror of people being forgotten. Writers can kid themselves thinking, “Oh, my work will keep me alive.” And, of course, that's not true. Most of us—writers, artists—disappear.

JE: I think that's an odd neurosis of writing—wanting to stop time, or bring time back, which is impossible, but writing is the closest thing we have to do it.

Maybe interviews are, too, or home movies or recordings—this desire to make things matter.

LT: Don't [writers] write a lot about time? We're always thinking about it. Nan Goldin made an incredible film that debuted in 2021 [called Memory Loss] where she uses footage that was shot when they were all young, in their early 20s, and most of the people in those films are dead. She uses answering machine tapes to punctuate the film as it goes on, and then at the end, it goes back to those people, those young people, dancing. It's tremendously moving. I think it's one of the best things she's ever done.

JE: I want to see that.

LT: I wrote about it for Frieze Magazine. It’s about 22 minutes.

JE: There is a line in this book where an editor in 2006 said, in a rejection letter for American Genius, A Comedy, “I don't know what Lynne is trying to teach me.” I found it oddly comforting. I sent it to Mesha Maren, who started Zona Motel with me. One of the reasons why we started Zona Motel is this despair we feel about our current moment in publishing. We read that quote and were both like, “Oh, maybe we’ve always wanted books to instruct us and hold our hands.” Because humans are narcissistic, and we always look at our current era and think it's the worst one ever.

Do you see any special, or particularly bad things, about this moment in publishing, or are we at a place that we've already been before?

LT: I've been very fortunate. My first full-length novel came out in 1987 and that was a good period. There were many different publishing houses, and different imprints within those houses, so there was a lot more opportunity.

There were 19 rejections of Haunted Houses, and things happened very randomly. I got word of somebody who might be interested, and I told my agent. She didn't know about this imprint. And that happened, and I was fortunate to have a publisher for three books, which was Poseidon Press, inside Simon & Schuster.

But what I learned was that salespeople work on commission, so they're not going to be pushing your book. If they have Stephen King or something to go out with, they're going to be talking about that book. So you're lucky if you get a salesperson who actually wants to talk about your book, and then maybe the bookstore takes five books. It's much more hierarchical in publishing. Who is your editor? If your editor has clout, you might get a little more money, things like that.

I was very unhappy with the design of most of my books. Barbara Kruger wanted to do my first cover. And [the publisher] said, “Oh, yeah, I understand this,” and then went with a kind of cover that had been used for Bret Easton Ellis.

Nan Goldin took my author photograph. Did they make it big? No, they made it little. They had no idea who Nan Goldin was. Being published by a smaller, independent press has been a much better fit for me.

I guess the most important thing to tell you is that I never stopped publishing in small magazines. The New Yorker or The Paris Review were never interested in my writing. I didn't even try. I didn't want to publish in so-called “big presses.” I felt that my readers, should I ever get any, would be likely to read independent presses. So that is a decision I made early on, not to wait for big presses.

TL: One thing I admired about you, Lynne, is that the machine doesn't stop. It keeps going.

LT: I mean, I'm alive. I live in the present. Obviously, the past affects the present, but I want to be, and am, in touch with younger writers. I'm interested in being in their magazines. I want to continue to be in discourse with [them]. I understand lethargy. I understand not wanting to try anymore. I understand wanting to “rest on your laurels,” such as they are, but that's not for me.

JE: I think that's a reason why I really admire you and your body of work. It’s not resting on your laurels, in terms of tangible things, but also stylistically. You’ve written, as you talk about in this book, so many different types of books. You’re always wanting to create something new, some sort of new problem for yourself, and that seems really ambitious. I admire that.

LT: Thank you. But let's not continue to compliment me.

TL: The whole process with Archway was organic. I didn't really go out and search for a publisher. It also had to do with my trips to New York City, participating in the scene, going out of my way to meet people, either in person or online, but I really felt devoted to blowing life into this project, pouring all my time into birthing whatever may materialize. So, when I initially sent a text to Chris Molnar, one of the editors, and he replied he'd be interested and that Nic was reading a lot of Lynne's work currently, that was enough to start putting everything together. There was no agreement that they were going to publish it. I just needed someone kind of interested, so I had an excuse to pour into it. It was a bit of a risk. But I was just like, “I think this will work,” and so I'm glad it did.

JE: That was one of my questions: how did it end up being at Archway? Because I feel like so many books, when you see them published, you don’t know their story. A lot of them have either this organic path, like yours did, or this very circuitous path of thinking, “It's going to be here,” and it's not.

LT: There's one other thing I want to say about publishing. I'm very fortunate. When Richard Nash had his imprint at Soft Skull, he took up American Genius, A Comedy, and nobody else wanted it. That comment [you mentioned] was from a woman editor at a well-known independent press. I found it to be so sexually prejudiced, not what she would have said to a male author. No, women are not supposed to teach. We're not supposed to know enough to teach. I thought it was disgraceful that she wrote me that, and I was very lucky that Richard Nash took the book, and then published a couple of others that nobody else would do. Who else would publish What Would Lynne Tillman Do??

To know that you have somebody interested in your work, and waiting for it is a tremendous gift. I think publishing in [smaller] magazines is very important for writers, because it may be a long time until you have a book. There's no community for a writer, for your writing. You speculate perhaps that there will be, but only your writing brings people to your work, right? They have to read it.

Lynne Tillman is a novelist, short story writer, and cultural critic. Tillman has received a Guggenheim Fellowship; a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, and was awarded the Katherine Anne Porter Prize by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2025, Soft Skull Press will publish her collected stories, Thrilled to Death. In 2026, Zwirner Press will publish a collection of her essays on art and culture. She lives in Manhattan with bass player David Hofstra.

Great interview

Love