INTERVIEW: The Monster at the End of This Birth Story: An Interview with Erica Stern

"I’ve always been plot-skeptical."

Editor’s note: Shayne Terry, who interviews Erica Stern, was interviewed by Erin Anadkat earlier this month. Both Terry and Stern recently released genre-bending books that recount their own difficult birth stories. I recommend reading both interviews, as they feel like one great ongoing conversation. When I was pregnant, a friend gave my unborn baby the Sesame Street Little Golden book The Monster at the End of This Book. Grover learns from the title that the book contains a monster and repeatedly begs the reader not to continue reading. The curious child laughs and turns page after page. The monster is lovable, furry old Grover, right?

Since giving birth, this is how I read birth stories. I keep turning the page, hoping the monster at the end will be a healthy baby — not a monster at all! But what if it’s not?

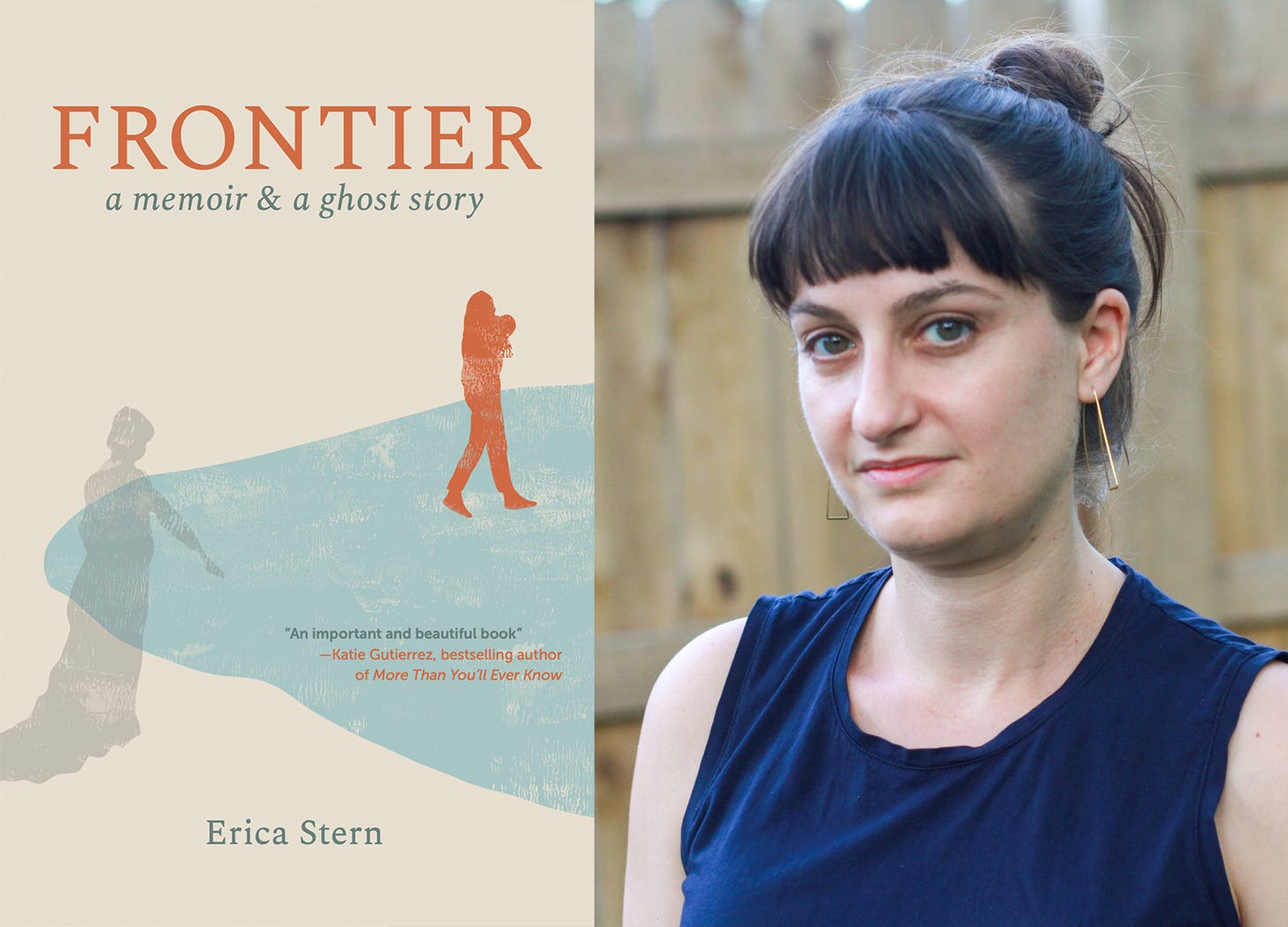

Erica Stern’s Frontier: A Memoir & A Ghost Story tells three tales. One is an account of the author's birth experience, during which her son Jonah experienced hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), a type of brain injury newborns can get during birth. Memoir passages alternate with chapters of a fictional story about a frontierswoman who dies in childbirth, along with her baby. Woven throughout is a researched history of the industrialization of birth.

The genius of Frontier is the way Stern uses genre tropes — ghost story, gothic, horror, western — to go where the traditional birth story can’t. Perhaps no birth story reveals all its monsters in the end, but Stern’s blend of memoir and fiction brings us closer to the truth. We spoke via video conference in early May.

Shayne Terry: How did the hybridness of the book come about?

Erica Stern: It was a complete accident. I started writing this book about a year after Jonah was born. I hadn’t written anything for a year, and when I went back to writing — I was still in my MFA program, and I had been writing short fiction — I was like, well, can’t do that anymore, not right now. This was the only story I could write.

At some point, fairly early in drafting, this idea came to me — what if I was a woman giving birth in the Wild West?

It started out with me imagining myself in the Wild West as a mother who’s given birth and undergone similar complications to what I went through. What would have happened? What would this story become? But then as I wrote the Wild West sections, she became her own character. I didn’t hold myself to what I would have done. I let her become separate from me.

I think it served two functions. Partly it was a counter to this discomfort with writing the personal and with writing the emotional, because it was an emotional strain to go back into this material. It gave me a break. I could leave reality and escape into fiction, which was my default mode since memoir was new to me. And also I was interested in the history of birth, and in exploring this thing I felt in the delivery room of not being part of modernity anymore and suddenly being closer to the past than the present.

ST: The book contains this palpable ambivalence about the medicalization of birth. You go into the ugly history behind the science, how many “breakthroughs” around pregnancy and birth involved the dehumanization of women, including brutal experiments done on enslaved women. And yet, it was modern medicine that saved your baby.

ES: Right after the birth, I had a lot of rage in all directions. I was furious with the home birth movement and the natural childbirth movement because I felt like those people were talking about this experience that was alien to me. What do you mean the body can naturally birth a healthy child and it’s made for this process and medical intervention is bad? Because I felt like medical intervention had saved our lives, and it had. We were lucky to be at a hospital with a great NICU. I think the injury was lessened because of how quickly they were able to intervene, so I was really grateful to be in a hospital.

But I was also angry at the doctors, because I felt like I had trusted them. I don’t say this because I think they did anything wrong, but I had gone in assuming that once you’re in the hospital, you’re safe. Things work out. You’re in good hands. I was being monitored, there was a nurse in the room the whole time, doctors in and out, so if anything goes wrong, we’re fine, we’ll have a C-section, it’s good. And that wasn’t what happened. So I felt this anger toward the system, too, that was supposed to protect me. And that was naive, of course. Part of why I wrote this book is because I believe birth is still dangerous and risky and we don’t talk about it.

As I was researching and getting into the history of obstetrics, I saw how complicated it all was. I strongly believe science is good and we should trust medicine but I started to see the misogyny that had paved the way, how male doctors have dominated this sphere for so long. How they took over for midwives years ago, or the way the naming of different things in obstetrics reflected this tarnished past. The racism too is undeniable.

So I started to see that this debate was more nuanced and more complex, and it allowed me to have more empathy for people who were arguing for less medical intervention. Their goal was to reclaim agency in this male-dominated system and I started to understand that.

I think there’s room for a balanced approach in the end. I hope that becomes more common, for people to understand that birth can be dangerous and we need medicine and we need science, but also that it doesn't need to come at the expense of women’s autonomy and respecting women — those things are not in opposition to each other.

ST: You did achieve a balance in the book, but I understand the rage in both directions. There’s also so much we don’t know, yet the medical establishment has no incentive to constantly remind you how much it doesn’t know.

ES: They don’t do any research on pregnant women. I use the term “black box” to talk about the uterus, which may seem extreme, but that’s what the doctors called it, because they know so little of what goes on internally during pregnancy and delivery.

There are things I’ll never have answers for. I’ll never really know what caused the HIE. I think with time that’s become easier to sit with.

ST: You write: “One of my first acts as a mother to a baby in my own home is to throw out the copy of What to Expect: The First Year.” I had the same anger at all the birth books, whose cheery advice seemed ludicrous to me after I’d actually been through it. None of them spoke to our unique circumstances. What do we need instead of these books?

ES: If I were just going to make edits to the books, I would say some real mention of the not-so-good outcomes that can happen. And not just like, “You might need a C-section” or something vague or general, but listing complications that can happen. Prematurity gets a lot of attention in these books, but there are other things. I didn’t know the name Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy until days after Jonah was born, because it’s not in any of these books. And it’s not common, but it’s like one or two in a thousand births in America.

ST: That’s more common than one would think!

ES: And birth trauma in general is super common. Anecdotally, I think most people who go through birth have some sort of birth trauma, and so real acknowledgement in the What to Expects of the world would be great. Going beyond surface edits, I’d love to see a general reframe of birth and pregnancy. This isn’t a trip to Disneyland. We’re adult women embarking on this huge endeavor. It’s going to change things. Books can acknowledge that. Too often they gloss over all the complications instead of treating women like adults who can face complicated stuff. I think there’s this fear of scaring women who are about to give birth, but I’d rather have a little bit of fear that’s grounded in reality. The books can and should trust people with that information.

ST: Instead of all the birth books, I wish I’d read more poetry.

ES: Your birth mantras should have been lines of poetry.

ST: Just a lot of Frank O’Hara. You know, there is one book I found helpful in the postpartum period because it actually deals with birth trauma, and that was Kimberly Ann Johnson’s The Fourth Trimester. I read it after my birth and I wish I’d read it before because it’s real and raw.

ES: I’m writing that down. I’m not having any more kids, but I’m still very interested in reading all of this material.

ST: Well now your book is becoming part of the canon!

Let’s talk about time. You show how our experience of time can be completely warped by birth, and the way this can change our relationship to linear narratives. We go to the birth/death portal and we come back with the conviction that narrative is simply not that easy, not that straightforward. “Event without warning. Warning without event. There is no plot,” you write. Talk to me about how this life experience affected the way you think about plot as a writer.

ES: I’ve always been plot-skeptical.

ST: Same.

ES: With my fiction, plot is usually the afterthought. The things I read are more meditative and internal, character-driven, voice-driven. In some ways, I think I was always looking for a more expansive understanding of plot. Plot doesn’t have to mean a huge amount of suspense; it can be small, it can be internal.

But birth did throw any semblance of plot and linear time out the window. The way you talk about the portal is so great because you’re coming up against something — and it’s death, and it’s life — and all of these binaries are suddenly jumbled. I feel like that’s true with time.

For me, plotlessness also had to do with being disembodied. I can only speak from my experience, but this probably happens even in relatively non-traumatic births, where you’re just disconnected from your body.

ST: You go to the animal place. I have talked to people who think of their births as non-traumatic and asked — did you go to the animal place, did you go to the portal, whatever you call it, were you there? And many people have told me yes.

ES: My portal was being in the vents. Floating up above the room and feeling that disconnect from the event as it was happening. I wasn’t part of the plot anymore.

ST: Have you read Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode? It’s a craft book that talks about taking plot patterns from nature. Instead of the traditional arc, with its masculine climax that peaks and then collapses, you can have plots that are spirals like a snail shell, plots that are waves, plots that are fractals. Very much in line with how you talk about plot in the book.

ES: There should be a chapter on the birth portal plot.

ST: Yes! And I also was not a plot person even before experiencing birth, but now…

I connected with your book so much because it was internal, voice-driven, and recursive. This repetition — we don’t leave things that happen behind, they stay with us.

ST: Because that’s how memory works. The brain keeps returning to things.

ES: And I found so much to pull from in what actually happened that supported my thesis about plot. This idea that the brain injury happened at a point during labor, but the brain could incur further injury when it started to recover. These things I thought had endings that were set in stone did not — that’s not how nature works.

Also, we both wrote a lot of our books in present tense, and I found that was the only way I could write about the birth. Because it’s still so present. I understand why it’s controversial to write a memoir in present tense, because you can’t reflect. But it also felt like the only true way.

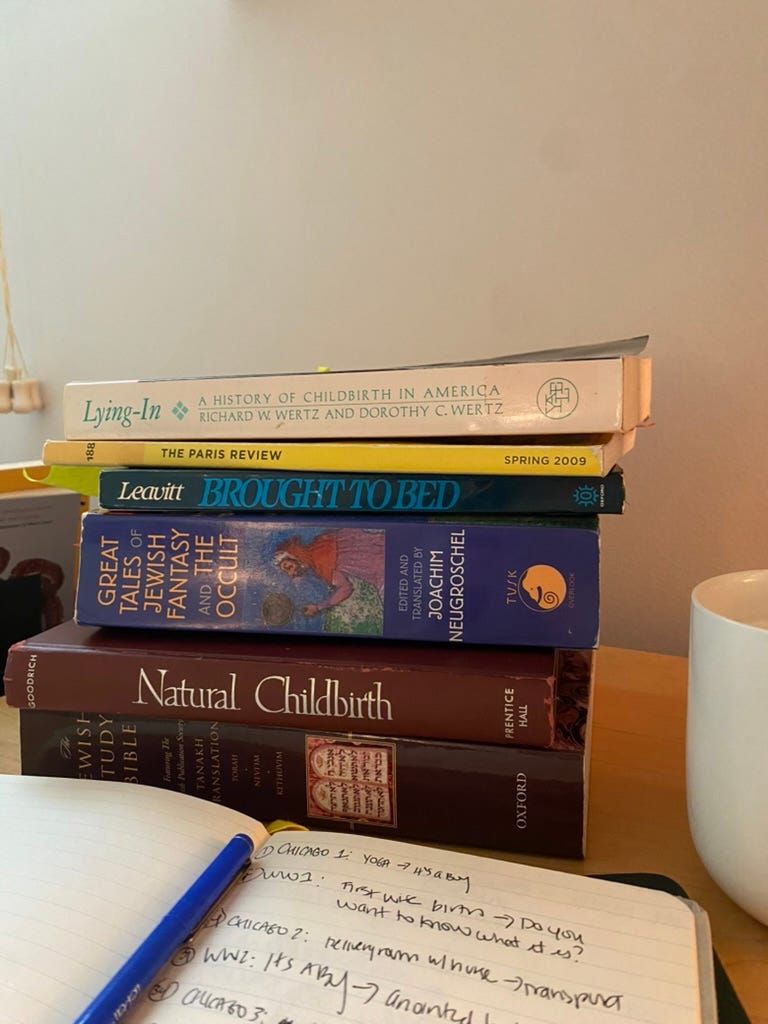

ST: Another thing I love about your book is all the research. You get into scientific history, religious philosophy, developmental psychology, and then of course there is the research that historical fiction requires. What was your research process like?

ES: This is the benefit of not being a journalist or an academic: I was really free to do the research that suited me. I was mostly telling my story and the accompanying fictional story, and I could bring in whatever research felt relevant. So it was a fun process. I read books about birth history, I read articles about the different medical procedures and diagnoses, I read books and articles about the Wild West. I think it served a similar function to the fictional thread — it was a way to escape the emotional intensity of the writing. I needed to go to fact, to go to history.

Also, I became kind of obsessed with birth. I wanted to learn everything about it, which sort of surprised me. I thought I would want to run away from the trauma but instead I wanted to dive into it. And research provided that window for me. I could funnel all the obsessive energy into research.

ST: And now this book about birth, birth trauma, and reproductive health is coming out in our present political moment! How does this feel for you?

ES: It’s a trip! Not in a good way. Right now with all this chatter about pronatalism, what I’m thinking about most is how the “pro-life” environment is actually making it scarier for women to get pregnant and give birth. What we’ve both experienced, and what so many women experience, is a real lack of control. So many things can go wrong. And we need to be able to trust doctors to make decisions to keep women and children safe. I’m also thinking so much about how cultural conversations idealize the role of women as mothers in this way that completely whitewashes the experience of pregnancy and birth. The end result is a devaluing of women’s lives.

ST: And in a lot of cases by women, which is the complicated thing about it to me.

ES: And now there is the attempt to get other women on board with monetary awards and other incentives… It all feels dystopian.

ST: Bad vibes about all of it. The place where I have decided to channel my energy is into things that actually help families. Right now in New York City we have a candidate running for mayor whose platform includes universal childcare starting at six weeks. I can’t even wrap my mind around how life changing that would be for so many babies and parents.

ES: And doing it not because you want women to have more children, not with some ulterior motive, but just because it’s the right thing to do. Meanwhile I just got an email from the ACLU of Illinois that the Head Start budget is under threat. We’re moving in the opposite direction in so many ways.

ST: After Leave was accepted for publication, I had this moment of doubt. Am I really going to put this story out into the world? Women’s stories and birth stories are so frequently devalued, it’s easy for the voice of doubt to have some real internalized misogyny.

ES: Like, “Nobody’s going to want to read about the female body.”

ST: Exactly. But having my book come out in 2025, all I have felt is yes, we need to be telling these stories, we need to be speaking up about what birth is actually like. What I have found — and I am certain this is about to happen with your book as well — is people have been reaching out to me and saying, “The same thing happened to me and I never told anybody about it,” or, “I finally feel like I’m not alone.” I’ll be the first to say it to you now: Thank you for writing about the things that can happen during birth.

ES: It’s not for the faint of heart, birth. This is the thing that gives me hope right now, in this moment: that women’s stories are getting told more. Yes, our stories are important and I’m seeing more of them in the world.