PROFILE: Sebastian Castillo's Fresh, Green Summer

Lucy K Shaw travels to Philadelphia to profile her novelist friend

When the editors at Zona Motel informed me I needed to go to Philadelphia to interview Sebastian Castillo, I tried to convince them it wasn’t necessary. I live in Europe. It would be a long flight. Expensive. We could just do it on Zoom for free. But no, they said, the publication is doing well. I should fly there and talk to him in person. Get the real story. All expenses paid. They said they wanted me to ‘try to revive the type of magazine feature that Esquire published in the 1960s.’ I thought they were joking, but then the PayPal notification appeared on my screen. Why me? I asked. We have colleagues in Philadelphia more than capable of conducting a conversation with one of their own. But they insisted it had to, could only be me. They said, I’m the one who has been there since the beginning.

Fine. I gave up my No USA 2025 resolution and got on a plane from Sevilla to Barcelona, then another onto Newark, New Jersey, from where I would take an American train to Philadelphia. On the first flight I reread The Zoo of Thinking, a recent chapbook of Castillo’s published by Smooth Friend in 2024 that collects a selection of his short prose. And on the second, I reread a PDF of Fresh Green Life, the new novel to be published this summer by Soft Skull. (Soft Skull, Smooth Friend, it sounds as though I’m just making these things up but they’re real.)

It was at 35,000ft, somewhere over Greenland, that I realised I should probably make some notes or start thinking of a few questions. I began by writing a timeline of his bibliography:

1988, Born in Caracas, Venezuela

2012, Published first story, Knife Man (Shabby Doll House)

2017, Published first book, 49 Venezuelan Novels (Bottle Cap Press)

2021, Published esoteric grammar experiment, Not I (Word West)

2023, Published absurd, comic novel, SALMON (Shabby Doll House)

2024, Published collection of short prose, The Zoo of Thinking (Smooth Friend)

2025, Published slightly less absurd but equally comic novel, Fresh Green Life (Soft Skull)

I found it satisfying to note the growing catalog. To witness a career that accrues meaning through accumulation. Nothing would make sense without 49 Venezuelan Novels. There could be no Fresh Green Life without SALMON. Not I might have been, as he went on to tell me, his “least popular book” but it’s an essential part of the journey.

It all began for me in 2012. I was running an online literary journal (Shabby Doll House) and though apparently submissions were closed, I received an email from a stranger with the subject line ‘hi’ that included the sentence, ‘I know your submissions are closed but I read that you guys were looking for stories, and so I figured I would send two short ones.’ Though addressed to you guys in the plural, I was, at the time, the only guy involved. Needless to say, I accepted one of the stories for publication and, as they say, the rest is literature.

I made a similar timeline of my personal history with Sebastian:

1987, Born in York, England.

2012, Published Sebastian’s first story, Knife Man, in Shabby Doll House.

2013, Met Sebastian in person at the Brooklyn launch of Taipei by Tao Lin. He approached me and asked if I was Lucy K Shaw, which I was. He said he was Sebastian Castillo, and I said, It’s a pleasure to meet you. We chatted briefly and after we said goodbye, my friend (Gabby Bess) thought I was famous.

2016, Invited Sebastian over for dinner at my apartment in Berlin while he was visiting his uncle who lived nearby.

2017, Blurbed his first book, 49 Venezuelan Novels.

Also in 2017, Sebastian helped to organise an event at a warehouse in Philadelphia where I read from my chapbook How to Be A Perfect Bride, a short book I wrote about my mother having cancer when I got married.

2018, Watched much of the World Cup with Sebastian and his friend Robert in Paris. England beat Colombia on penalties at a bar in Belleville. We drank a lot. His mother had died very recently from cancer.

2020, Started the ~Profound Experience of Poetry Book Club and read many books together for the next three years.

2021, Started writing about my life in the pandemic and emailing it to some friends. Sebastian told me I should make it into a book, so I did. It’s called Troisième Vague.

2022, Sebastian was meeting his father, who he had not seen in thirteen years, in Madrid. (His father lives in Venezuela.) I suggested he write a book about this, and he emailed one to me several weeks later. This book, titled Iyashikei, is actually my favourite of his to date, though as it has never been published, I did not include it in the bibliography.

Also in 2022, Sebastian asked if I would want to publish his novel SALMON, which I had read and loved a few months earlier while he was still sending it out to bigger presses. I listened to his voice note while I was walking down a hill towards a supermarket in Crete and said yes, in my mind, before I knew what he was going to ask.

Also in 2022, Sent him the manuscript of my book, Woman with Hat, which he had also encouraged me to write. I remember walking around Budapest and exchanging long, detailed voice notes about our various manuscripts in progress.

2023, Published SALMON and travelled to Philadelphia again for the launch at Iffy Books.

Also in 2023, Attended the wedding of Rachelle Toarmino and Aidan Ryan in Buffalo and spent a lot of time on the sofa, late at night, watching iconic live musical performances on YouTube. I enlisted Sebastian’s help to convince Kristen Felicetti to publish her novel with Shabby Doll House as part of Operation Convince Kristen.

2024, Following the success of the operation, Sebastian joined us on the subsequent book tour in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Brooklyn, where he invited Kit Schluter to read on his behalf, to a backyard of adoring Castillo-heads.

2025, Travelled to Philadelphia again to interview Sebastian before the release of Fresh Green Life, his fifth book, and his first on a press run by more than one person.

We had arranged the date and time for our interview (May 29th, 2025. 12pm ET), but I hadn’t actually told him I would be travelling to his country, to his home. I suppose he assumed I would send a Zoom link, but instead I just knocked on his door at the exact time we were due to meet. After a brief wait, he opened it slowly, cautiously, as though he had not been expecting to use it in this manner. Sebastian appeared before me in socks, faded uniqlo trousers and a vintage, 1988 Team USA Olympics t-shirt. He looked briefly startled, then pleased.

“Wait — are you… actually here?” He asks, adjusting his glasses.

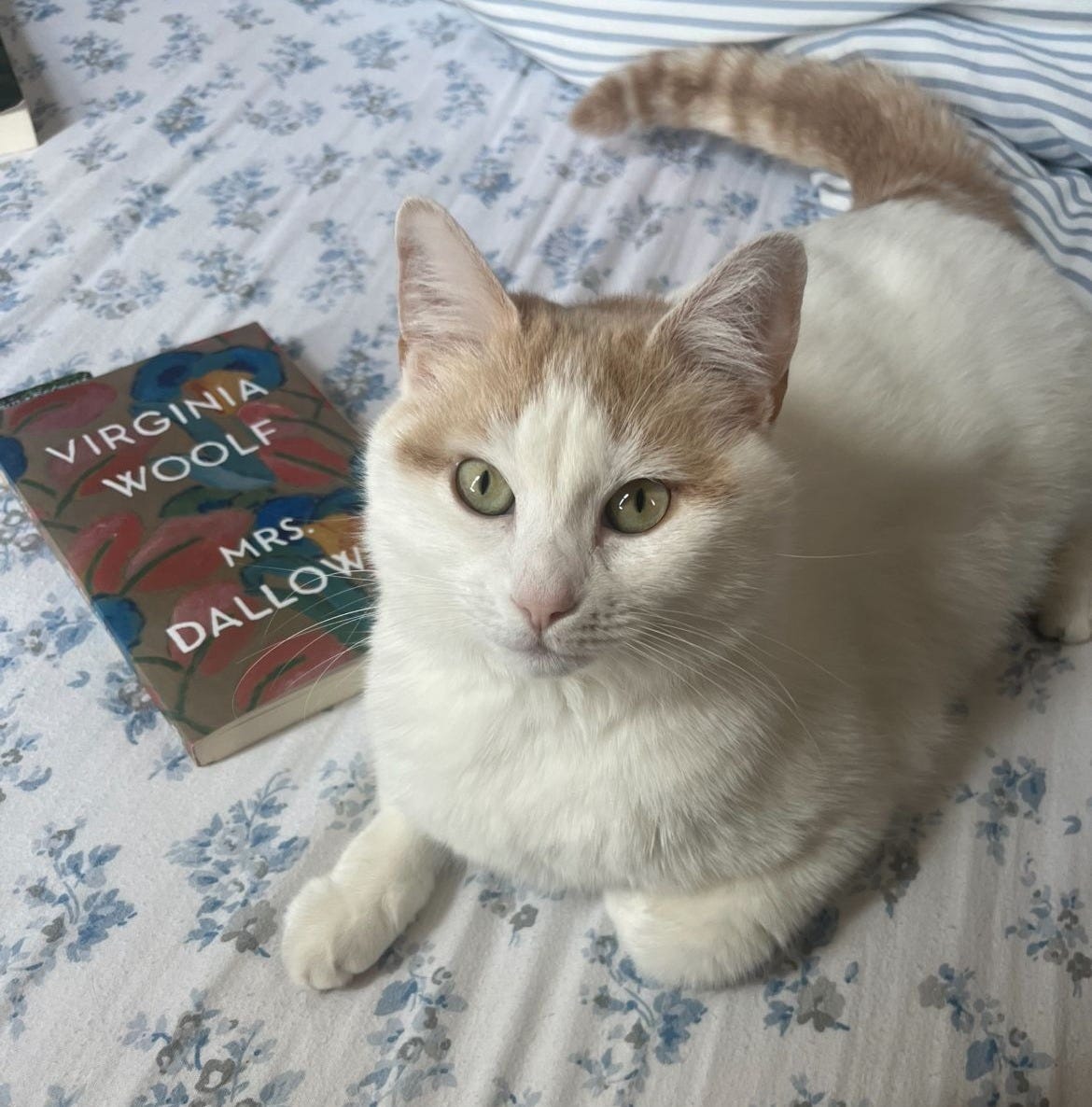

The cat, standing behind him in the hallway, peers out as though equally surprised.

I reach out my hand and place it on his right shoulder.

“No,” I respond, completely deadpan, “ I’m a figment of your imagination.”

He smiles and welcomes me inside. I haven’t been to this apartment before. He moved less than a year ago, and is living alone. I greet Millie, the white and ginger cat named after his grandmother. A woman he once described to me as very meek. I remember running in Paris one day, listening to one of his voice notes, and in particular the detail that his meek grandmother Mildred’s favourite food had been peas. Millie the cat is not meek at all. She wants a lot of attention and Sebastian seems more than happy to provide it.

He offers me coffee but I don’t drink coffee so I politely decline, and we catch up as I scan the apartment. Guitars. A piano. A poster of Robert Grenier’s poem-map, Cambridge M’ass. A lot of books, a lot of shelves. Mrs Dalloway clearly in progress.

“I'm reading it because I saw on Twitter that it was published 100 years ago this month. A few weeks ago, I saw the same thing for The Great Gatsby, and I realized I had not read The Great Gatsby since I was 16, when I was in high school. I was then 36 and I said, wow, it's been 20 years. So I'm going to reread The Great Gatsby, which I enjoyed. It's a little melodramatic toward the end, but it has a really pleasant style. And so then when I saw the thing about Virginia Woolf, I said, well, I've never read Mrs. Dalloway, so I think I owe it to Virginia Woolf to do the same.”

Sebastian is the kind of person who thinks he owes something to Virginia Woolf, and he’s probably right. I ask him about his usual schedule and he tells me that if it weren’t for the fact that we had arranged a conversation in the middle of the afternoon, he would otherwise have been at the Temple University library, writing.

“I like going to this one in particular, rather than to a much closer public library because in summer it's pretty empty, there are just a few students, who I assume are taking summer classes, milling about, but it's fairly empty and very, very quiet. I like to go there and get into a little cocoon chair that feels kind of private. My plan originally was to go from 10am to 3pm every day. But actually, I find I have a word count that I try to hit, typically about 1500 words. Sometimes I go over it. Sometimes, like yesterday, I did 2000. One day, I even did 3000 which is quite a lot for me, and I kind of find that after a certain amount, even if I know what I'm going to write next, even if I have this outline, the quality of the sentence degrades a little bit, or it just becomes a little bit more perfunctory, a little bit more he goes here, he does this, you know, and I just feel like it's better to stop at that point, especially if I know what I'm going to do next, because that means that when I go back the next day to sit down, there's not even a moment of hesitation or writer's block, because I already know.”

Ernest Hemingway said the same thing in his Paris Review interview in 1958, so it must be effective. Sebastian teaches at several universities during the academic year, but it’s late spring now and he’s making time to work on his next novel. “I just finished the fifth out of eight chapters that I've planned,” he tells me. And I don’t think I know anybody more prolific. Fresh Green Life is due out in a matter of weeks, yet instead of switching into a publicity mode, he’s chipping away, a couple of thousand words at a time, towards a new completed manuscript.

I ask if we can go to the library so I can see where he writes, and he says we can either take the subway (Broad Street line, north), or drive for twenty minutes because he “has a parking pass that’s good for the whole summer and we can park in the garage.” I mean, this is America. In the car, I ask him about his upbringing. It might seem improbable but this man was raised by ballerinas in Caracas.

“I grew up pretty much exclusively speaking Spanish, and my parents spoke English at home because they wanted me to be bilingual, but I would only respond to them in Spanish, at least according to them. I mean, I don't remember this very well.”

As we move through the city, I’m struck by the disparity in the scale of everything. South Philadelphia, where Sebastian lives, feels like a rare, walkable European-inspired neighbourhood with low rowhomes and local independent businesses, artisanal coffee shops and natural wine bars interspersed with long-standing, generic establishments providing products from another time. Dishevelled people in their thirties wearing glasses, denim and a certain style of tattoo drift vaguely through the streets as though unsure of their purpose.

But as soon as we drive into Center City, gravity shifts. The buildings grow by several stories, the vehicles around us seem to expand, even the pedestrians look like they mean business. We pass below a mammoth billboard advertising the services of a so-called ‘accident attorney,’ and I feel like Alice in Wonderland. I’m shrinking, I think. But I have to remain focused.

“Did your parents ever encourage you to do ballet?”

He checks his rear-view mirror.

“No, my parents never pushed anything on me like that. They never said, okay, you need to try dance now. And I think a part of that is because they were both so voluntarily dancers. They had this sort of fire, like they really wanted to do it, both my mom and my dad, and so I think they understood that that drive is a really necessary component of being successful, because it's such a physically and psychologically demanding profession.”

He pauses and I almost (but don’t) point out that he clearly has their same drive towards writing books.

“And so they just sort of let me do my thing. I mean, when I was a kid, they would bring me to performances. And I remember back then, the only thing that I was interested in was the music. I loved listening to the music that accompanied the ballets, but I didn't really care so much for the dancing.”

At this point, I note that the car doors are stuffed full of CD sleeves and an eclectic mix of house, hip hop and ambient jazz has been providing our soundtrack.

“It’s not that I want to be old fashioned — it’s just that the car has a CD player and so it’s easy to make the mixes. I date them by month and year so I can pick out a random one and can say, “Alright let’s see what I was listening to in August of 2019”

Like many of us, Sebastian came to writing through music.

“Yeah, I was obsessive from the age of 13 to my early 20s. I practiced guitar all the time, played in a lot of bands, and tried to record a lot of music with friends. I always enjoyed reading, and that was always my best subject in school. But I wasn't necessarily driven by it, or I wasn't obsessive with it, and it was only in, you know, my college years, I guess you can call them, or in my early 20s, that I became much more of a fervent reader and I realized that I could try to write. By the time I was in my mid 20s, I still enjoyed playing music, but I cared more about writing and literature.”

We pull into the parking garage and he looks for a space on the second floor.

Fresh Green Life’s protagonist, much like Sebastian, teaches at a university in Philadelphia. He’s also named, interestingly enough, Sebastian Castillo, though he’s not, as you might imagine, the Sebastian I’m currently sitting in the car with.

When I first started reading the novel, I worried there might be something particular about the academic setting, the collegiate atmosphere, that would alienate me from the narrative. University, for me, was not a defining moment, and it ended sixteen years ago. Whereas this character, our narrator, just like Sebastian, is immersed in the academic lifestyle. I couldn’t relate, but thankfully I didn’t need to. The Sebastian Castillo in the book gradually revealed himself to be a total lunatic, and then I didn’t really care where he worked.

I note the smell of heat and rubber in the stale air as we get out and walk down to street level, and I realise this was the first time I’d been in a car for weeks.

“The biggest inspiration for Fresh Green Life was thinking of the act of narration as the event. How a person's thought tracks and evolves over the course of several pages. Compositionally, that was how the book came about. I started with the first paragraph. And every single time I sat down, I just wrote one paragraph following the preceding one. And I didn't have a rule, but, my idea was I would just take some thread of thought from the preceding paragraph and use that to talk about something else.”

And what does he want to talk about? We’re hovering outside the library now, aware we’ll soon have to be quiet.

“For many years, I've been obsessed with new year's resolutions, and I make them every year. And I typically, to my credit, follow through on a lot of them, not all of them, but a lot of them. I was questioning this aspirational tendency that I have. What do I hope to achieve, you know?”

We’re smiling because we have no idea.

“It made me realize that I often have this future version of myself who's figured out all of these things and therefore they will be self actualized, in the future, but it'll only be once I'm fluent in Spanish and I can play Bill Evans on the piano, and whatever. And, of course, that's a total fiction. And it made me think about all the stuff we're surrounded by that tries to sell that fiction to us. Like, in terms of wellness culture: Take a cold shower every day for 30 days, and you're going to be transformed as a person. You're going to be the person that you always should have been. I mean, a lot of that stuff seems corny and hacky, and like only a dupe would fall for it. But actually, there are all of these ways that someone who should ‘know better’, falls for it, but gives it a different story, or a different way of framing what they're doing. And so I wanted to place that contradiction in an absolutely bizarre manifestation of somebody like me, which is, of course, why I gave him my name.”

This is Sebastian’s second novel to contain a character named after himself.

“I just thought it was funny because there's nothing really in that person's life that resembles my own, other than the fact that they're also an adjunct.”

I narrow my eyes suspiciously. I can think of a few other ways that this character resembles the real Sebastian, or examples of how the character’s emotional texture resembled his own life at the time of writing, and I put them to him, off the record, as we walk into the library and sit down on some benches in the lobby area. No spoilers. But after a little pushing, he does concede:

“I mean, I'm definitely interested in autobiography as a way of approaching literature, and it’s something that animates my attraction to literature, but it's always going to be through a kind of a strange mirror. John Ashbery does that a lot with his poems. He often writes autobiographical poems, but they're just so bizarre and formally playful. And you would never guess that it was necessarily autobiography, but so many of his poems mention his rural childhood in upstate New York.”

John Ashbery would have loved Fresh, Green Life.

(You can use that, if you’re reading this, Soft Skull.)

Sebastian walks over to a vending machine and returns with two cold seltzers. I take a large sip and make an exaggerated “ahhh” noise of satisfaction to signal my gratitude.

We agree to meet in an hour and he heads off to his cocoon chair. I remain in the lobby and make another list.

Fresh Green Summer means:

Spending your free time at the library writing 1500-2000 words a day.

Adopting a cat and naming it after your grandmother.

Reading books published a century ago.

Monthly mixes for your car’s CD player.

Showing up unannounced in another country when your interlocutor expects a Zoom meeting.

Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror

A couple of hours later — he’s written 1800 words of his new novel and I’ve written the opening few paragraphs of whatever this is. It’s mid-afternoon by now and I feel like a Kardashian, the way I’m describing this in present tense.

I’m literally at the library with Sebastian.

We get back into the car and play a mix CD from June 2023, the month SALMON was published, and I feel a little proud of us. For collaborating on that book, of course, but also for how long we’ve sustained this friendship and working relationship and for having written all of these things together. I used to think a lot about this Hemingway line from A Moveable Feast: “There is not much future in men being friends with great women although it can be pleasant enough before it gets better or worse, and there is usually even less future with truly ambitious women writers.” (He was talking about Gertrude Stein.) I don’t think it’s true in our case, (I mean, why would it be?) although of course I have known other men who get intimidated, or dismissive. With Sebastian, it has always just felt like mutual belief.

We decide to stop at the supermarket, back in South Philadelphia. I want one of those yerba maté sodas you can buy in America, and Sebastian wants:

coffee beans

eggs

Greek yogurt

sparkling wine

In Pennsylvania, grocery stores can only sell alcohol if they make you pay in a separate place, as though you’ve wandered into another business by mistake. I don’t really understand what’s going on but I’m stunned by the prices. Back in Spain, I could have bought five or six bottles of wine for the price of one. And I feel briefly stressed until I remember Zona Motel is paying. What would we have done with six bottles of wine anyway? As I’ve mentioned, we’re hardly Hemingway.

I lose Sebastian among the brightly lit aisles and go to wait outside. The store is named ACME, like the bomb manufacturer in Looney Tunes. And there’s a plaque outside commemorating that this was the site of Pennsylvania’s last public execution by hanging in 1916.

When he emerges I say, “I didn’t know they used to hang people at the grocery store.”

He must be loving this. He thought he’d talk to me on Zoom for a couple of hours and then continue on with his life, but now I’m just here, asserting my Europeanness. I say I’d like to go for a run and he says he was thinking of going to the gym. I ask him what he does at the gym and he tells me, “today I’m doing back and biceps.” We return to his apartment, change our outfits and agree to reconvene in the early evening.

As I’m running through his neighbourhood, I think about how I’m going to write all of this down. What kind of profiles did Esquire actually publish in the 1960s? What kind of budgets did those writers have access to? What about those essays Alice Notley wrote in Coming After about her friends’ poetics? Or Ron Padgett writing entire memoirs for his friends after they died? If I don’t write a five thousand word profile of Sebastian Castillo when his fifth book comes out, then who else is going to do it? How will anybody in the future know that all this happened? How will we remember?

It’s that perfect time of year, before the concrete gets hot, and flowers and weeds bloom out of everywhere, even in a city like this, where tonight the sky looms large and grey over its residential streets. Beads of sweat slip down my shins. The empire crumbling around me. I didn’t want to come to this country this year. I find it too exhausting to exist here, too expensive in too many ways, though I remember I didn’t always feel like this. I think about Venezuela, which to me feels so far away, distant, dream-like. And I try to place Sebastian on a map of the world in my mind. A little boy on another continent, speaking another language as the Earth turns. And then a man who reads books and writes novels appears here, fully-formed.

I wanted to run 10km but I get lost and it turns into eleven. I stop by the ACME supermarket again to buy a neon coloured sports drink and a bunch of cheap flowers for my host. The sun lowers to let an orange-pink complexion break briefly through the clouds and I realise it’s 2am to me. I let myself back into Sebastian’s apartment, take a shower and get ready to go out while I wait for him to come back from the gym. I’m using my phone camera as a mirror to do my make-up as Millie pads quietly around the living room, sniffing my tote bag and settling nearby. I listen to some of the audio I’ve recorded from our conversation earlier in the day:

Lucy: Do you have any memories of your personality as a child in Venezuela?

Sebastian: Yeah, I think I was very much a ham. I think I was very playful and silly, and liked being the center of attention, being talkative, and I liked drawing a lot and that kind of thing, which is funny, because I guess I grew out of it. I don't think of myself in those terms at all anymore. I'm more reserved now, but I had a kind of playful and free spirited childhood.

Lucy: And then you moved to the United States when you were eight years old. Had you visited the US much before that?

Sebastian: Yeah, almost every year for Christmas, my mother's family was very big on Christmas gatherings. It was the one day of the year when everybody gathers. Everybody would travel to my grandparents place, and so I don't remember most of these occasions, I mean, because I was very young, but I would say at least probably five times or something, I visited the United States, and typically, for a period of about a month, it wouldn't be a brief visit. And I remember really loving it and enjoying it. And I even remember having dreams about it. When I was a kid back home in Venezuela, I dreamed about going to New York again, because I liked it so much.

Lucy: So when you found out that you were moving there, I guess it was because your parents were separating?

Sebastian: My parents were separating, and my mother got a very good or at least, you know, relative to her life in Venezuela, got a good job offer for a dance company in Manhattan. It sort of coincided that their relationship was falling apart, and she got this great job offer, and so,

Lucy: It was like a way out for her.

Sebastian: Yeah, yeah.

Lucy: And how did you feel about leaving?

Sebastian: I was very upset the first month or so, I cried a lot. Mostly because I missed my father. But I kind of very quickly got over it. I feel like children are very resilient with that kind of thing. I made friends in the United States very quickly, and within the first few months, I just sort of felt happy to be where I was.

Lucy: And do you remember... well, obviously you spoke English already, but did you feel like you needed to reinvent yourself in that language?

Sebastian: Yeah. So the two things that happened were that I was technically left back a grade when I came in. I should have gone to the third grade, I think, and they put me in the second grade because they said he's not totally fluent in English. And I was also put into ESL classes, but I pretty quickly graduated out of them because I already had a background of hearing English at home. But it was kind of, I always talk about this period as sort of funny, because at that age, you know, a year makes a difference. So I was the tallest kid in class for three years until maybe about the sixth grade, and then everybody else had a growth spurt.

Lucy: Did you remain a year behind the whole time?

Sebastian: I did, yeah.

Lucy: And did you feel very aware of that as a teenager? Did that feel strange? Or was it okay?

Sebastian: I feel like at that age, you associate being older with somehow being cooler, or, you know, if anything, I enjoyed being a year older than all of my peers, and especially when I turned twenty-one, all of my friends were very happy because I could then buy alcohol for all of them.

Lucy: I imagine, as you were a teenager, and you got further away from having lived in Venezuela, it might have even felt hard to explain, if someone asked you, why are you a year behind? The reason might have seemed unbelievable.

Sebastian: Yeah. I mean, that conversation happened a lot.

Lucy: You seem, to me now, extremely American. Do you feel like you made an effort to be this way?

Sebastian: No, I think it happened totally naturally. You know, in that everything about my life was just surrounded by American culture. One of the things that I did most as a kid, my mother worked in Manhattan and she would get off work around six sometimes, and then she would have to commute home, and so it would take an hour. And I had from 3pm to 7pm or so to myself, which I actually loved. It was like a feeling of great freedom. I spent a lot of that time, especially in the first few years, just watching American sitcoms on TV, like reruns of TV shows. And so all of the things that I was absorbing at that age were American culture. And so I think that transformation was pretty organic, but severe. And also because I lived with my American family and had gradually less contact with my father's side of my family. I lost a lot of connection to Venezuelan culture.

Lucy: Did you have an interest in Venezuelan or other Latin American culture? Hispanic literature or music or sports, or you know, just anything that kind of tied you to it?

Sebastian: When I was a kid, no. I would visit Venezuela every summer until I was about maybe 12 or 13. So I went back a few times. And I would stay for six weeks or something during summer vacation, I would stay with my father. But then I stopped going. It was mostly an issue of money, flights to Venezuela became increasingly expensive. And then my mother, she was a very anxious person, and she was worried about crime in Venezuela and didn't want to send me alone, that kind of thing. And so I just stopped going. But at that age, I was more interested in my immediate surroundings. I was interested in video games and Pokemon cards or whatever. I was never interested in sports. So that was not something that was a part of my growing up. I would actually say it wasn’t until my early twenties, that I developed a kind of renewed interest in, you know, reconnecting with, if not Venezuelan, then at least South American culture at large, mostly through literature, a little bit through music, and yeah, I feel like that's not an uncommon thing for... I grew up with a lot of friends who were Brazilian, and they had a sort of similar trajectory, where growing up, they became very American, but then once they hit their late teens, early twenties, they all of a sudden developed an interest in becoming Brazilian, more Brazilian than they had been. And that's something to do with that age, when your sense of identity becomes more important to you or something, and so you try to recreate yourself.

I hear the front door open and a moment later, Sebastian himself appears in the living room, his back and biceps appearing strengthened. I’m just kidding. Although he does seem refreshed after a long day of recounting everything that’s ever happened to him.

We walk to Solar Myth, a cool, quiet, dimly lit jazz bar nearby that Sebastian goes to regularly. The bartender asks if he wants a negroni and he bashfully accepts. I order a pilsner because I’m hungry, and then notice tomato and spinach pies on the menu so we ask for one of each of those too. By this point, we’re both kind of exhausted by talking about everything so seriously, and I say I’ve probably got more than enough material to write something. He laughs and says, “I feel like I’ve shared my entire life story.”

He asks me a lot of questions about what I’ve been working on, and it feels good to talk about that too. It feels healthy to remember how to have a regular two-way conversation. Sebastian says he thinks I should prioritise my own writing for a while, that I should write a book this summer and start working on publishing new ones by other people later, which feels liberating, like getting permission. I feel grateful for the moment, for the conversation, for the magazine, for the friendship, and for the prospect of all this fresh, green life.

Zona Motel did not really pay for me to go to Philadelphia. That was a lie. <3

I am ready to live my best Fresh Green Summer

This was the greatest thing I’ve read all month. Thanks for putting in the money to fund Lucy and her visit across the planet