ESSAY: Amazon Reviews, Bots, and Democracy

I am old enough to remember when Amazon mostly sold books. The launch of Marketplace, which allowed for third-party sellers, happened just before I graduated high school. Suddenly, I could access used books quickly. I knew, even then, that Amazon was at least partially evil, but it was also kind of revolutionary. Before Marketplace, if a friend recommended a book, I would either place an inter-library loan request, which sometimes took months or failed altogether if the book was obscure, or I would go to Downtown Books and News on Lexington Avenue in Asheville and scan the new arrivals shelf, shoving aside the masses of Bret Lott and Barbara Kingsolver novels in search of Genet’s lesser-read titles. Using libraries and local bookstores was much more sustainable for the literary ecosystem but it was also frustrating. I was growing and learning at a fast pace, and I wanted to read the Bilge Karasu novel now and the Etgar Keret collection the next day, and with Marketplace I almost could.

Amazon’s shift toward becoming the “everything store” seemed like it happened slowly and then suddenly. With the diversification of its offerings, Amazon became a place to browse and research potential purchases instead of simply a broker, and with that the importance of reviews grew. Amazon had offered customers the ability to review their purchases from the very beginning, but the importance of reviews for sellers burgeoned in the mid-2010s. In 2017, Amazon implemented the Early Reviewer Program, where brand-registered sellers could pay $60 to enroll a new product and have Amazon incentivize shoppers to leave a review in the form of a low-value gift card. In 2019, they launched the One Tap Review system, allowing customers to leave a star rating without actually writing a review. In 2020, they added a “request a review” button next to customer orders in Seller Central, allowing sellers to solicit a review in just two clicks. During this time, “brushing” (the practice of sending unsolicited packages to a person’s address to create fake orders followed by fake positive reviews) flourished, and at least six merchants were charged by the US Government with conspiracy and wire fraud in relation to bribing Amazon employees to manipulate product reviews. Reviews had become so important that sellers were willing to do almost anything to up their numbers. In 2021, Forbes reported a 138% lift in conversion rates (the percentage of website visitors who complete a desired action, such as making a purchase) when shoppers interacted with reviews.

Now, in 2025, the customer review is undoubtedly king, which might seem like a win-win for shoppers and merchants, but when it comes to books the situation is trickier. Books are not products in the same way that say rice cookers or vacuum cleaners are. We all use vacuum cleaners to suck up dirt, and we want our vacuum cleaners to suck up the dirt efficiently. We might want the vacuum to be lightweight or have a long cord, but we don’t expect the vacuum to say, cook our ramen noodles for us. If someone left a customer review of a vacuum saying, “defective, not very good at cooking,” we might laugh but we would all understand that this was not a problem with the vacuum. But people don’t buy or read books for exactly the same reasons. Reviews for art, including books, are a much more complicated matter. Do you even know why you feel compelled to read? I’m not sure that I do.

I engage with professional reviews of art for the experience of seeing the art through someone else’s perspective, coming to know the way their brain interacts with the art. I don’t read professional book reviews to determine whether or not I should purchase a book. Sometimes, as a result of reading a review, I do purchase the book, but not because the reviewer told me the book will provide me with X, Y, or Z. I purchase the book because, through the review, I get a sense of the texture of the book and I feel excited by that texture or mood, usually for unidentifiable reasons; some aspect of the review made me feel that my mind would like to interact with the text and so I buy or borrow it.

When I published my first novel in January 2019, my (then independent) publisher said nothing to me about Amazon reviews. When I published my second novel in January 2022, the marketing folks at Algonquin (owned by that time by the Hachette corporation) sent me an email asking me to “get my friends and family to leave reviews on Amazon.” This felt deeply embarrassing and quite frankly wrong and so I ignored this suggestion. When I published my third novel in May of 2024, the marketing folks at Algonquin/Hachette sent me a barrage of emails with tips on how to coerce my friends and family into reviewing my novel. This made my stomach sink, and I again ignored them.

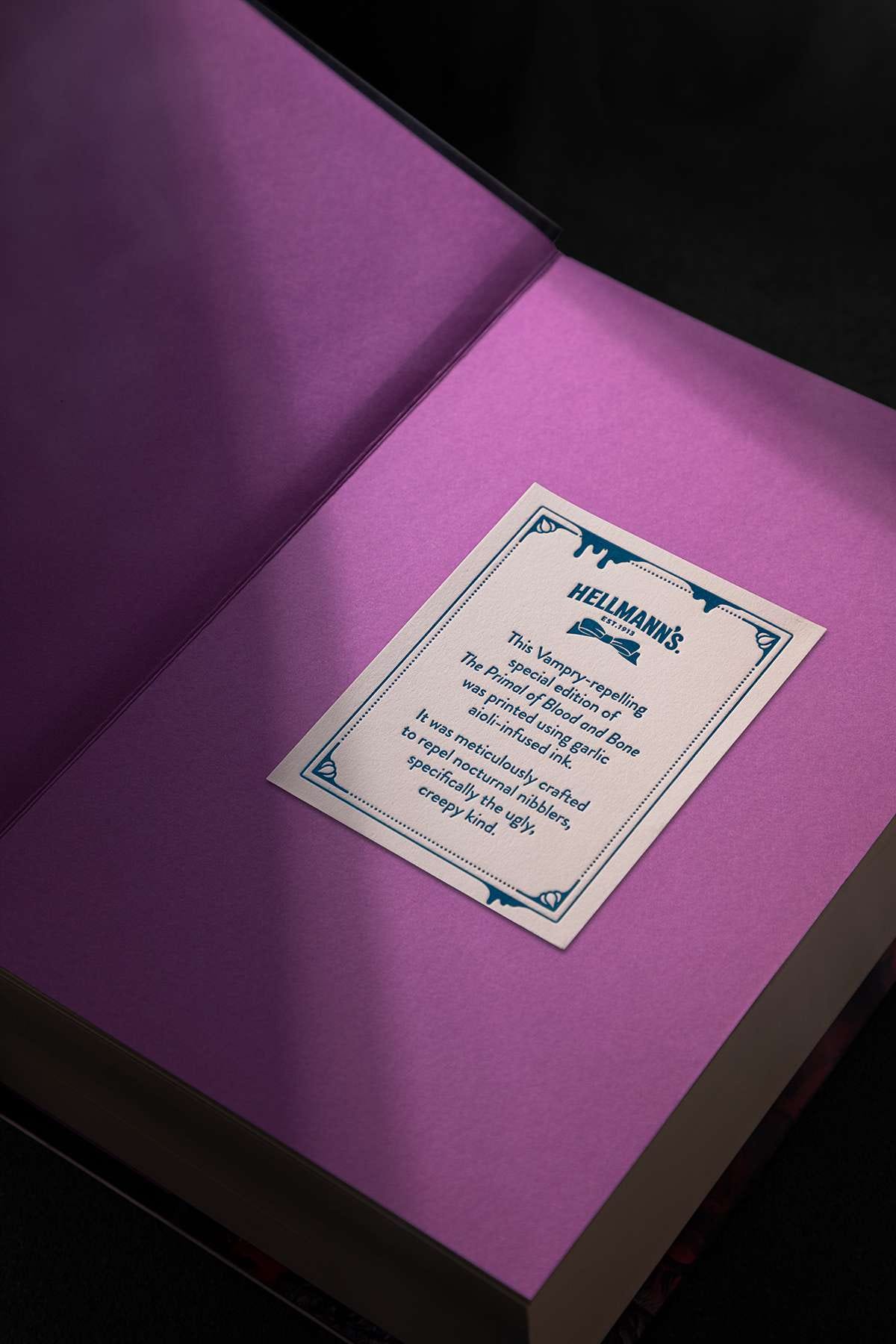

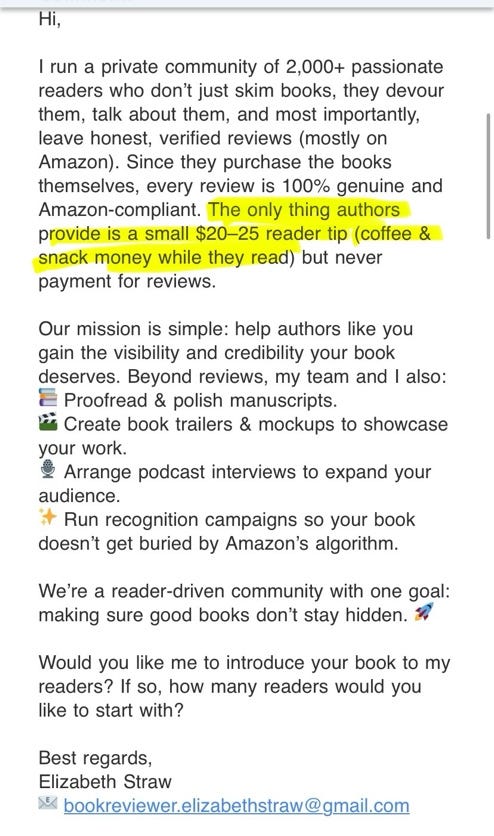

Shortly after the publication of my third novel, I also began to receive regular rounds of emails from people selling Amazon reviews. They all claimed they were not selling reviews but rather soliciting “tips.” I ignored these emails too until one day in September when I was bored and fed up and waiting in line, and I received the following note:

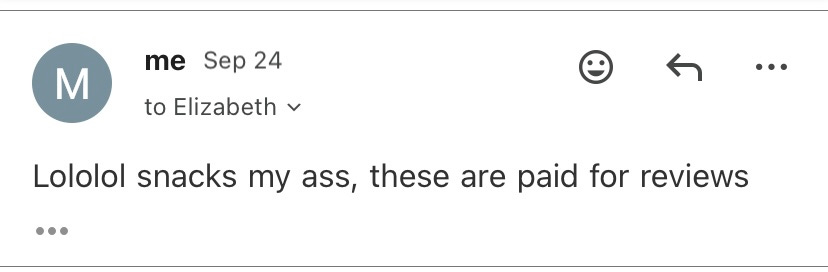

As I said, I was bored and fed up and waiting in line, and so I responded:

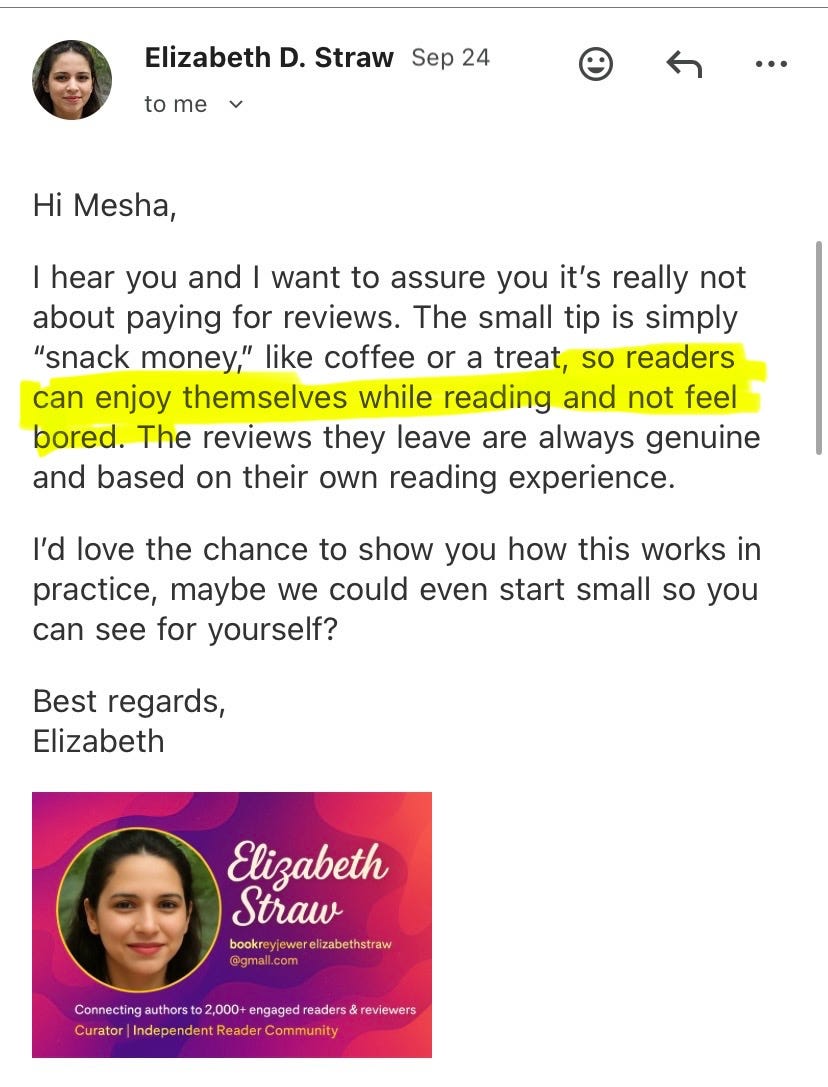

And to my surprise, “Elizabeth” (I am 99.99% sure “Elizabeth” is a bot, or if not, she is at least using a bot to write her emails) responded:

At this point, I think I snapped a little bit because I began sending “Elizabeth” consciousness-raising manifestos day after day.

9/26/25

Elizabeth,

I think we got hung up on the snacks, and the snacks are not really what I care about. The snacks are a distraction. What I care about is the death of criticism and true discourse as it is currently occurring through the commercialization of book culture. Everyone knows that the professional book review is dying (or already dead?) This has occurred as a result of many different factors, but one of those factors is the growth of the supposed importance of customer book “reviews” such as the ones that you are peddling. I am not concerned that you are bribing people to read books but rather that so-called “reviews” like the ones you are making money off of are killing off professional critical reviews and deep, intelligent essays about art. In the words of film critic Richard Brody, “In downgrading reviews, publications yield to the temptation of corporatized impersonality, just as much as tightly formatted and studio-governed Hollywood movies do. Arts coverage risks becoming a spectacle unto itself, the creative vitality of individual voices replaced by a smorgasbord of packaged samples.” Part of the confusion in the conversation that you and I are having probably stems from the word “review” which, much like the word “essay,” has a range of meanings. You mean a 500 word max (that is Amazon’s limit) thumbs up or thumbs down with accompanying stars for easy digestion. I mean a reflection on a work of art “with perspective on the history of an art form and an awareness of its current state—an awareness developed by the immersive diligence of writing reviews on a wide range of recent events” (again Brody’s words.)

I am not personally offended by the fact that you reached out to me. I am enraged over the fact that schemes like yours are further eliminating professional reviews.

In the words of freelance critic Kristen Martin, who recently articulated on Substack the important difference between reader reviews and professional reviews:

“To think is to make judgments based on knowledge: period. For all criticism is based on that equation: KNOWLEDGE + TASTE =MEANINGFUL JUDGMENT.1 The keyword here is meaningful. People who have strong reactions to a work—and most of us do—but don’t possess the wider erudition that can give an opinion heft, are not critics. (This is why a great deal of online reviewing by readers isn’t criticism proper.) Nor are those who have tremendous erudition but lack the taste or temperament that could give their judgment authority in the eyes of other people, people who are not experts. (This is why so many academic scholars are no good at reviewing for mainstream audiences.) Like any other kind of writing, criticism is a genre that one has to have a knack for, and the people who have a knack for it are those whose knowledge intersects interestingly and persuasively with their taste.”

Again, my distate is directed at your “tips for reviews” scheme and your leechlike attachment to a system that commercializes art and reactions to art and throttles real discourse at a moment when deep discourse is needed more than ever. Schemes like yours that focus on the entertainment and consumer value of art will eventually contribute to the deterioration of our very Democracy. In the words of George Packer, “Twenty-first-century authoritarianism keeps the public content with abundant calories and dazzling entertainment.” I hope your readers enjoy their snacks and entertaining reads on their ride to autocracy!

Best,

Mesha Maren

“Elizabeth” promptly assured me that the “snack money” (note she herself put the words in quotation marks this time) wasn’t “meant to devalue [my] work at all, it’s simply a lighthearted way we’ve found to keep readers engaged and excited while they read.” She then proceeded to once again pitch me a paid-for Amazon review.

9/27/25

Elizabeth,

Wow, I called you a leech on democracy and you said, “so, I’m hearing that you’ll take one paid book review?” I gotta say, I like a girl who doesn’t know when to quit.

The snacks continue to distract, as snacks are wont to do, but here’s the thing: your business model feeds off of the current state of book culture, which relies almost entirely on authors’ labor. You didn’t approach my publisher with your offer of paid reviews. My publisher does this kind of thing, “giveaways” or bookstagram campaigns or whatnot, and that’s fine, I don’t care, but I also don’t involve myself in it at all. But notably, you did not reach out to my publisher; you reached out to me. Authors are inherently vulnerable, and you are using this vulnerability to make money. I don’t feel particularly vulnerable because I don’t care about Amazon reviews at all, but there are many authors, particularly self-published or micro-press authors, who hope that if they work hard enough, a bigger press will pick them up. And the bigger presses often do this (take the book Theo of Golden as an example), by “this” I mean that the bigger presses pick up books and repackage them after the author has worked tirelessly to promote and publicize the book on their own. These enormous corporations are using the labor of micro press authors, and it is deeply fucked up, and you are a part of this ecosystem. You are capitalizing on the inflated value of a customer review, and it is disgusting. Real reviews are not about selling books (that is one potential outcome, but not the primary reason for their existence.) Real reviews are about discourse. You are making money off a system that equates art with consumerism. Consumer reviews are for vacuum cleaners, not art.

Best,

MM

Elizabeth assured me that the “snack money” was not a bribe! She follows Amazon’s review rules, she insisted. The “snack money,” she said once again, was “truly just a small gesture to make the experience more enjoyable.” She then offered me a discounted review and invited me to her Discord group, where I could meet her “top readers.”

9/28/25

Elizabeth,

“Always Be Closing”- am I right? Hahaha. Joining your Discord group sounds like a special version of Hell. No, thank you. I will not be paying you for any Amazon reviews because customer reviews of art are worthless. Customer reviews of things like vacuum cleaners work because we all agree on what a vacuum cleaner should do- suck up dirt. Art does not work like this. As John Warner said in a recent Substack, “the way we respond to books is enormously specific and idiosyncratic. We are, each of us, a ‘unique intelligence’ and when our unique intelligence collides with the unique intelligence of another in the form of, say, a novel, that collision creates a reaction that will never be the same for two readers. Similar, yes, but not the same.” Some people read books to uplift themselves, some people read books to escape reality, and some people read books because they like the rhythm of a certain writer’s prose drumming in their brain. No two people ever want a book to do exactly the same thing, and so a customer review is not only entirely useless, it is damaging because it threatens to narrow down the experience of reading, to turn the book into a tool, the way that a vacuum is a tool with one simple purpose. Literature does not have a singular purpose; that is what is beautiful about it. The customer reviews you are peddling are particularly dangerous right now because the publishing industry is in the midst of a self-made crisis. As Taija Issen writes in The Walrus, “Despite widespread conversations in 2020 around equity in publishing, we’re witnessing a general retrenchment in the industry. Decision makers are adopting an even more conservative stance, which steers them toward acquiring books from people who already have built-in audiences—like celebrities or influencers. Sales track—or simply track, in industry parlance—is an invisible force shaping contemporary literature. Much depends on that number. On the basis of track, publishers and struggle to keep going; those just starting out fear their careers will be severed at the root. Track shapes how an agent pitches a book and how editors assess whether to buy it. Track restricts reader choice by dictating which books are served up as the next big thing (and the next, and the next) and by kneecapping writers deemed insufficiently commercial. The primacy of track, in other words, is a barometer for the health of literary culture. Right now, when the industry is especially skittish, the obsession with finding the next blockbuster hit privileges the survival of the few at the expense of the many.” Publishers have stopped believing that literature is important in and of itself, as an exploration and reflection of humanity. They have begun to view literature as simply one more product in the capitalist system. They now value literature only for the money it can make them. The reviews you are peddling contribute to this view of literature as a disposable product, one that needs to be constantly waved in front of potential consumers’ faces and accompanied by snacks in order to entice them.

You are contributing to, and making money off of, the death of art.

Best,

MM

“Elizabeth” assured me of the high standards of her quality readers. “Many,” she said, “go deeper than a quick star rating!” Every morning, in my inbox, there was another note from her, insisting on the purity of her motives, but our epic correspondence finally wound down when I brought it back around to the snacks.

10/01/25

Elizabeth,

You gotta understand that no one can possibly take your supposedly sincere efforts seriously when you charge money for snacks, “so readers can enjoy themselves while reading and not feel bored.” These are your very own words!!! “Not feel bored”- WOW. It speaks volumes that your readers need snacks in order to “not feel bored” while reading : )

MM

To my surprise, “Elizabeth” admitted that she had made poor word choices. “I can see why you reacted strongly,” she wrote. “What I meant wasn’t that readers need food to avoid being bored, that was clumsy wording on my part.” And then even more shockingly, she (temporarily) stopped bothering me2.

For about twenty-four hours after this final message, I felt satisfied. I had gotten the bot to leave me alone. But my own mind would not leave me alone. I kept thinking about the fact that during my own forty years of life, the role of books in our society has been turned upside down. When I was born in the early 1980s, literature was considered by the U.S. government to be ideologically powerful enough to be used as a weapon in the Cold War. The CIA spent thousands of dollars reproducing and distributing free copies of the novels of Virginia Woolf, as well as books by Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, and newspapers like the Manchester Guardian Weekly. They funded underground publishers behind the Iron Curtain and disseminated paperbacks of The Gulag Archipelago throughout Soviet countries. What I find most striking about this is the recognition by the U.S. government of the power of literary works. George Minden, head of the CIA Book Program, called it an “offensive of free, honest thinking.”

When Ursula K. Le Guin accepted the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014, the transformation of literature from a mind-opening work of art to a consumer product was almost complete, and Le Guin was aware of this. She said in her speech that night:

Right now, we need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art. Developing written material to suit sales strategies in order to maximize corporate profit and advertising revenue is not the same thing as responsible book publishing or authorship. Yet I see sales departments given control over editorial…And I see a lot of us, the producers, who write the books and make the books, accepting this —letting commodity profiteers sell us like deodorant, and tell us what to publish, what to write.

The recent consumer-reviewification of book coverage is obviously an outgrowth of this shift toward the development of written material to suit sales strategies. The entire literary ecosystem is dependent on the belief that literature is more than a product to be sold, the belief that books have inherent value as works of art—a value that can never be summed up in sales numbers. Once we lose sight of this understanding, the whole ecosystem collapses like a house of cards. If books are only valued for their sales numbers, then there is no reason to publish any book that strays from a predictably lucrative form. If books are only valued for their sales numbers, then there is no reason to pay critics to analyze them as art. If books are only valued for their sales numbers, why even have human beings produce them?

We find ourselves, in 2025, in a dangerous moment. Our cultural and literary critics are giving corporations like Airbnb mining rights to their minds (“mine the writing brain of The New Yorker essayist [Jia Tolentino]”) and People Magazine is doing more book coverage than almost any other platform at the moment (over the past three days I have seen three novels with advertisement-style write ups in People but with almost no professional reviews). In an interview with the Guardian, Chris Kraus spoke of the adaptation of her novel I Love Dick into an Amazon Prime Video TV series and she said, “To me, success would have been like a long review in the New York Review of Books, not being a character on a sitcom.” Kraus’s statement felt like a breath of fresh air, but I fear that we are losing sight of this kind of perspective and losing it fast.

Because I could not stop thinking about the relationship between Amazon reviews and the devaluation of art, I wanted to speak to a professional critic, to ask if this link that I saw was real. I emailed Kristen Martin, freelance literary critic and author of The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow, who recently put out a wonderful Substack piece called, “What is book criticism for?”

Martin was kind enough to engage with me over email.

Kristen Martin: I’ve also been hounded by these Amazon book review people lately (I’m an author, too), and it’s totally maddening. I’ve recently been beset by scammy emails from people promising Amazon reviews for my own book, and I think you’re spot-on in calling them leech-like. I got into it with one of them, whose subject line was particularly insulting (”The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow… and Neither Will Amazon’s Algorithm Without Reviews”) and designed to prey on insecurity about my book’s sales. I ended up blocking his email address because he simply would not stop responding to my requests to be left alone. He didn’t get to the part of his pitch where he asked for money for the reviews he was promising, but I’m sure that’s where it was going. The idea of these people wanting authors to pay $25 “so readers can enjoy themselves while reading and not feel bored” is insane-making. Not feel bored!!! That’s what the book itself is for!!!

I definitely do not believe that people who write reviews on Amazon or Goodreads or wherever should be paid. Reviews on those sites are pretty much all about people’s personal opinions and tastes, and often end up revealing more about them than the book in question. I don’t think such reviews even function well as consumer-facing guidance—they’re often so personal that I don’t think they can help people make decisions about what books they might want to read. (Of course, I say this but the bad reviews of my book on such places refuse to leave my brain.)

An environment in which we treat books like consumer products—and put any real weight on consumer-style reviews—does lead to the devaluation of professional criticism and of art more broadly. I’m not sure we can definitively draw a line of causation between the rise of Amazon and Goodreads reviews of books and the shrinking space for and investment in professional book criticism in journalistic outlets. But seeing the New York Times Book Review use space that they once dedicated to substantive single-book reviews for columns like “Let’s Help You Find Your Next Book” or the massive crowd-sourced “100 Best Books of the 21st Century”—in other words, this shift to a recommendation-based service journalism focus—is really disheartening. To me, that shift betrays an editorial belief that we need to chase readers’ whims and individual tastes rather than reckon with the book as a work of art and intellect deserving of critique on its own terms and in context of the larger body of work it belongs within.

Mesha Maren: You make such a good point about the New York Times Book Review‘s gift guides and crowd-sourced lists. It is not just the inflation of the supposed importance of Amazon reviews that is shifting the landscape of book coverage, it is also the fact that mainstream media has given over most of the space they used to set aside for the exploration of literature to consumer purchase guides which are harmful both to professional reviewers (as we saw with the AI-generated syndicated summer reading list) and to the books they purport to be promoting, as these guides diminish the roles of both reviews and books to their most crass function as capitalist products. As I said to the Amazon-paid-for-review lady this morning, customer reviews are great for vacuum cleaners but not for art. And of course, this consumer-reviewification of book coverage is happening within a literary ecosystem that is turning more and more into an assembly line for capitalist goods. In Tajja Isen’s article in The Walrus (which I read because you shared it on Substack, thank you!) she points out that sales numbers are the main way that books are chosen by publishers which feeds back into consumer reviews (if a book is chosen only or primarily because it looks like it will sell well then it will be promoted like a disposable consumer item) which feeds back into books being acquired for sales track. It is an endless loop.

Yesterday I read Joanna Thomas-Corr’s “The Booker jury is right, there are too many bad novels (and I should know)” where she says, “There seems to be a crisis of confidence about how literary fiction is sold without the kind of searchable tropes #enemiestolovers or #cunningfemmefatale that helps genre fiction to connect to its audience.” I agree with some of what Thomas-Corr is saying, but when I read this line, I thought, No, the problem is not that publishers have lost confidence in selling literary fiction; the problem is that they are too focused on short-term sales. Not all that long ago, I feel like publishers saw themselves as the purveyors of culture. You don’t sell vacuum cleaners because you believe in the transformative power of a vacuum cleaner. You sell vacuum cleaners to make money. But books used to fall into a different category. I think that publishers have lost confidence in books as a means for human exploration and reflection. They now see them as simply a way to make money. I am curious if you have thoughts on this.

It seems to me that it is no coincidence that within one year, both the chair of the Booker Prize and the chair of the Pulitzer Prize have said of the books submitted that they were “a waste of time” and “homogenous, inert, inexpert, cheap.”

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, “the age of vulgarity is upon us.” I wonder if you see this extending into the book world? I want to be careful because vulgarity can be great (I can’t see the word without thinking about how it was applied to William Eggleston’s incredible photography when he first began showing his work.) But I have always found it to be very vulgar how publishing has become so taken up with conversations about money—agents and advances and adaptations. And how publishers have begun using the news of the insanely large amounts of money that they spend to acquire books as advertising (why would the amount of money a publisher paid make me want to read a book?)

In her Times piece Thomas-Corr says, “to voice a taboo, do we honestly need more than roughly 31 good literary novels each year?” and I want to say YES, we do need more than 31, but what we don’t need is for all of them to be bestsellers. I would rather live in a world replete with good literary books that are expected to each sell modestly instead of one where there are just a dozen that sell and sell and sell.

KM: I’m so glad you brought up that Tajja Isen article from The Walrus because I really can’t stop thinking about it. Her reporting really articulated what I find most frustrating about the publishing industry lately, as an author, critic, and reader—that the way a book performs in the market seems to be the main thing that matters to major publishers. That’s well and good for people who write and read romantasy (or Harry Potter fanfiction or whatever is trendy next), or for Fox News guests and anchors writing political books, or for celebrities or self-help gurus, but it’s terrible for just about everyone else. I, too, would much rather live in a world that’s filled with many good literary books, both fiction and non, that have less pressure put on them to sell endlessly—and where authors of such books who don’t sell like gangbusters are given the time and space to develop their craft and publish more books.

As far as conversations about money in publishing go, I do think that it’s nuts that we use the size of a book’s advance as a marketing selling point. (Also, that often backfires—remember the “Cat Person” advance debacle?). But at the same time, I think it’s important for authors to talk among themselves about what they’re getting paid. Writing is labor! As my friend Ilana Masad pointed out in a recent essay for Electric Literature, writers “have needs too—they need to be able to keep a roof over their heads, clothes on their backs, and food on their tables. They need to have the time, space, and means to expand their horizons and enrich their imaginations via whatever methods they choose. They need, in other words, an income.” I could not have written my book without receiving the advance I got, and yet even though I had what Publishers Marketplace calls a “very nice” deal, that advance was in no way sufficient to cover my needs over the course of the four years that it paid out.

And as a freelance critic, transparency about money is even more important. Ilana and I are both members of the Freelance Solidarity Project (a division of the National Writers Union), and we collaborate in the Cultural Critics working group, where we organize around improving pay and working conditions for freelance critics. In 2023 and 2024, we collected data on freelance critics’ rates (through FSP’s excellent rate sharing tool) and found that about a third of critics are being paid less than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour per project. The median rate was $16.67 an hour, which is still below the living wage in most cities. We can’t expect to have a robust critical environment if rates are this low.

So yes, I get really depressed when I think about publishers treating books solely as a means to make money. But at the same time, the people who write books and write about books (and the people who edit them, produce them, promote and market them, etc.), need to be paid sustainably for their labor!

MM: I one hundred percent agree with what you are saying about transparency around money. We cannot improve anything if we are not transparent. In her 2014 National Book Foundation acceptance speech, Le Guin talked about “responsible book publishing” and I think what I want to ask you is, in your opinion, what would responsible book publishing look like?

The answer to this question is probably different for every single writer but more and more often I find myself thinking about open communication and respect. While writing is labor, absolutely, and writers need incomes, I never approached the publishing of novels with the expectation of bringing in an income regular enough to be my sole source of money. I did however approach the publishing of novels with the expectation that my publisher would respect my art and communicate directly with me about their process for bringing the physical object into the world. This has not been my experience at all as of late (ever since my once-independent publisher (Algonquin Books who was fantastic) was bought by a Big 5 (Hachette (a bookstore owner recently told me “we call them Hach-shit”lol)).

My maybe final question is, can we band together as authors and book critics and what would that banding together look like? Do we refuse to work with publishers and media outlets who treat us like shit? Can we shame them into caring about something more than money or is that a pipe dream? Do we just need to create more of our own responsible publishing houses and media outlets?

KM: I’d also put open communication and respect at the top of my list for defining responsible publishing. I think the complaint I share with pretty much every author I’ve spoken to who has put out a book in the past few years is that we wish our editors were more candid with us when it came to really basic information, like providing an accurate timeframe for when they would turn around edits. I fully appreciate that this lack of communication is often rooted in the fact that so many editors are overworked and underpaid, and they’re also tasked with essentially being secretaries for higher-ups who don’t know how to make PDFs, etc. But I think that we all deserve to be candid with one another, and that open communication signals respect for the working relationship and for the author’s labor as well. Delays in edits also mean delays in when the author will receive advance payments for delivery & acceptance and publication! That material reality for the author needs to be honored.

I would hope that candor would extend to explaining what’s going on internally at an imprint. My book is also from a Hachette/Hach-shit imprint, Bold Type, which publishes in partnership with Type Media Center, a journalism/nonfiction nonprofit that supports work that “addresses injustice and inequality, catalyzes change, informs and uplifts social movements, while transforming and diversifying the fields of journalism and publishing.” From the time I signed with them to the time my book came out, a lot changed with Bold Type and with the imprint group Bold Type is part of, Basic. A few months before my book came out, the longtime publisher of Bold Type’s sister imprint was pushed out, and then Basic announced a new conservative imprint helmed by a Heritage Foundation senior adviser. I cannot adequately express how much this disgusts me! I feel that these changes impacted how my book was treated internally, but no one who worked on my book actually told me as much. I’m sure they didn’t want me to worry! But I wish I knew more about internal conversations about marketing, publicity, and sales resources and how they were being allocated across the imprint group. And also, it feels taboo or even dangerous to say these things publicly!

In terms of your final question, I think we need to band together! One way is through union work. Though labor does stupidly limit how independent contractors like freelancers and authors can challenge companies—we can’t collectively bargain—there are other things that we do at FSP/NWU that allow us to hold those in power to account. We have a grievance and contract division that helps writers chase down payments and resolve work-related injustices. We’ve struck agreements with a variety of outlets (e.g. The Nation, Jewish Currents, etc) that spell out worker-friendly freelance principles/contract and rate language for all freelancers, not just FSP/NWU members. We’ve been active in lobbying for Freelance Isn’t Free legislation across the country. These are all ways that we push media outlets to care about more than money.

I think that the publishing house situation is trickier in that it requires a paradigm shift for authors to think of themselves as laborers, too, and to fight for more of a say in how our work comes to fruition. It’s tough because it’s of course a dream to be able to publish a book, and it’s easy to feel that when that dream comes true, we can’t rock the boat by asking for more than what we’re being given. Plus, the work is so solitary and siloed, and there’s so much opacity and secrecy surrounding traditional publishing. But I think it would behoove us as authors to talk more with other authors from our same imprints, imprint groups, and publishing houses, and to think about how we can work together to raise standards and improve our working conditions.

Writers and Critics Unite! A Statement on Industry-Wide Cuts to Cultural Criticism

Here Martin is quoting Daniel Mendelsohn.

I eventually had to block “Elizabeth” in order for the correspondence to truly end.

obsessed with elizabeth/your interaction

I'm imagining three ways forward for artists, critics, and patrons.

The first is for everyone involved to professionalize their work using sensible industrial standards, e.g. generous contracts, prompt timetables, clear communication, fair compensation, etc. Call it the Nordic model.

The second is for the connection between money and art to be severed as completely as possible. We can imagine with the latter option that the remaining artists are either independently wealthy (fine, but also likely responsible for a lot of boring art), members of the working poor who make art that is distributed mostly locally, or those who can persuade rich people to bankroll them. Call it the feudal system.

The third, and the least explored, is more anarchic. Shifting and overlapping groups of artists associated by affinity, geography, age, ethnicity pooling resources in a project-oriented way. More art co-ops, share houses, squats. Temporary online networks that then vanish. Crowdfunding (a.k.a. project-oriented mutual aid). Artists whose aim is to replace the institutions which once supported them not with similar structures with better standards and practices, but with new organizations which are dreamt, discussed, and determined by the artists themselves. Call it the dual power system.

I fear that power is so centralized, and that its aims are so crude, that reaching for the professionalization of the mid-20th century is doomed. And that the likeliest future is the feudal system. But I'm really hopeful more folks feel confident enough to experiment with the third way outlined above.

Thank you for this piece, Mesha. I'm glad you're sustaining your attention on and care for how artists can live a dignified life today.