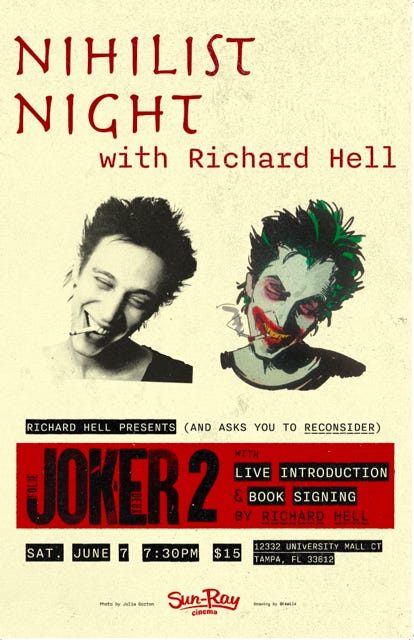

REVIEW: THAT'S ENTERTAINMENT: Joker II (Folie à Deux)

Richard Hell defends nihilism as a worldview and the Joker movies as 21st-century noir

With thanks for enabling this piece to Tim Massett and Shana David-Massett at Sun-Ray Cinema, Tampa, FL

I originally halfway intended to write a defense of Joker I in 2019, when it was released, but I didn’t get around to it. It turned out that on its budget of $60M it grossed a billion dollars worldwide, so a defense against its many contemptuous critics didn’t seem as urgent. It even won Oscars. But the sequel, which came out last fall, was even more heavily excoriated by intellectuals, and it cost $200M to make and was a disastrous box-office failure. I liked it even more than the first one, so I decided to speak up.

Part of the reason I was especially curious about the two Joker movies was that critics called them nihilist. In my latter years I’ve come to think of myself as a nihilist, without attaching a lot of weight to the term. For me, it’s not about fine philosophical distinctions, it’s just a convenient way to refer to the realization that life has no meaning, and that people ultimately can’t help who they are and what they do.

This point of view disturbs some because they read it as an ominous shirking of personal responsibility, but I don’t see it that way. Yes, this lack of meaning is a haunting fate (to use the operable word), but it’s not a justification for amorality and anarchism. After all, it denies the possibility of personal agency altogether. To me there’s a pathos in the situation that entails a deeper compassion and empathy for us all. And anyway, as much as I sense or deduce the universal absence of purpose, I, like everyone else, can’t help but to naturally, spontaneously understand myself as making decisions and trying to do the right thing.

I could accept the establishment and high-brow critics throwing the term “nihilist” around in relation to the films, but I didn’t like the derisive, scornful tone. I assumed that they had been overreacting out of a fastidious and self-righteous political reading of them, and when I saw Joker I, it seemed confirmed. The use of “nihilist” was partly intended to equate the movies with the chaos and relentless viciousness of Trump and his billionaire associates and lackeys. I resented that. Trump is a purely self-serving thug mob boss, a simple bully, without the wit to qualify as nihilist. He doesn’t have a metaphysics, only a compulsion to dominate, no matter the damage done. Whereas I, I’m a proponent, or scientist, of soulful nihilism, loving nihilism :-) and I’d like to rescue the word from its taint by association with Trump, and restore some clarity regarding these two dark, moving, cartoony, very smart, and magnificently crazy movies. They are both very good 21st century films noir.

Noir is my favorite cinematic genre, as it is for many movie lovers, and I like the Jokers the same way I like Touch of Evil or Kiss Me Deadly, classic noir in which everybody loses and all is futile.

A typical review of Joker I from the traditional press would be what critic A.O. Scott at the New York Times wrote, as summarized in its sub-heading: “Are You Kidding Me? Todd Phillips’s supervillain origin story starring Joaquin Phoenix is stirring up a fierce debate, but it’s not interesting enough to argue about,” referring to, as he put it, the film’s “brutal nihilism.” Scott objected to its defiant acting-out of deprivation, distrust, resentment, and anger. He thought it was exploitive and irresponsible, that it hadn’t properly earned the right to be so ugly and sad. I understand this kind of reaction because I feel the same way about certain other directors, like David Fincher (7even, Fight Club, Zodiac, Panic Room, etc.), who has always felt frivolously, smugly sadistic to me, rubbing audience’s noses in cruelty and pain to no purpose but to profit from the cheap thrills of the casual gruesomeness. You know, intellectually pretentious versions of the same motivations behind such as, say, the Human Centipede or Saw movies.

But it is possible to recognize the lack of meaning in life and react not with a drive to indiscriminately destroy, but with compassion, with kindness and goodwill towards all of us deprived, lonely, forlorn, death-destined, laughing beings. The most fun and unexpected quality of the second Joker is how it goes even further into hopelessness and despair than the first, thereby alienating even devoted fans of the previous film. You have to love it. Yes, maybe the love has a certain element of taunting the prim, but what the fuck? No harm done.

The Joker movies are art, and, regardless of their budgets, a free sort of art, with jazz-like values, as Phillips has said1, however expensive this flexibility may be under the circumstances (multi-thousands of dollars an hour on set). They’re wildly constructed and partially improvised. Joker I was a group improvisation taking place in a certain register, and riffing on certain milieus, namely the wastes and squalor of Batman’s Gotham City as New York in the era of Taxi Driver (1976) and the original punk bands and Bernie Goetz and his subway retribution (though in Joker the revenge is from the underclass directed at the smug entitled rich, rather than an apparent privileged racist one directed at rowdy, confrontational black kids, as Goetz’s was), namely the NYC of the 1970s and early ’80s, mixed in with another, separate riff on Scorsese of that same period, playing off quasi-psychopathic fantasies of becoming famous as a stand-up comic per Robert De Niro as Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1982). These allusions and collagings are not just legitimate, they’re inspired and fun. Obviously, many great works of art have elements of riffing on other artists’ work, especially in the last fifty years (so-called “post-modernism”), but it’s been going on forever. An obvious example is Shakespeare, who got his plots from pre-existing literature. Works of art are always communicating with other works of art.

Another reason critics were so angry was the budgets of the movies. It offended them to see Hollywood in the persons of Phillips and Phoenix (as Arthur Fleck/Joker) spend the 60 million dollars they did on the first production to immerse us in poverty, cruelty, and clown-faced gore. I think those critics would be wiser to direct their anger at Ronald Reagan and the Bushes and Donald Trump, the rich people undergirding our situation where it’s only their friends who can succeed. NOT that I’m saying the movie is a timely liberal protest film, not at all (that would be boring as fuck), much less a politically sophisticated critique. Income inequality has also existed since the beginning of recorded human history. It’s almost a given, unfortunately. The implications of the flick and the Fleck that I’m describing as noirish are perfectly reasonable interpretations. Also, in a capitalist society, if a $60M movie can earn a billion dollars, it will be made. Don’t blame Todd Phillips. It’s Phillips pointing out how horrifying it all is underneath.

Because life isn’t pretty, no matter how many Disney movies you watch. Life is hard, and cruelty perpetuates cruelty, and unbridled capitalism—pure greed—encourages meanness. In fact one meaning of meanness is greed, is stinginess. It should also be pointed out that the nearly universally admired Taxi Driver itself features a “hero” (Travis Bickle, who like Arthur Fleck is in an Art Flick) whose act of mass killing not only goes unpunished, but appears to have been highly therapeutic for its perp, given how he appears, at the end of the movie, to have finally attained a peace of mind, a degree of serenity, by way of his murders. Not a joke. That’s what happens in Taxi Driver.

Scorsese, in fact, was for a long time during Joker pre-production considering being involved in the movie. He might have signed on as a producer, or even director. He eventually decided against that, and when asked why, after the release of Joker I, he carefully explained, “I thought about it a lot over the past four years and I decided that I didn't have the time for it. […] It was personal reasons why I didn't want to get involved. But I know the script very well. […] For me, ultimately, I don't know if I make the next step, which is to this character developing into a comic book character. You follow? He develops into an abstraction. It doesn’t mean it’s bad art, but it’s not for me.”

When I first read that quote, I didn’t get quite what he meant by “abstraction,” but on consideration I got the drift, though for me it’s not a detriment. Yes, comic book characters are abstractions, they are caricatures, they are brands, so to speak, but that also has its own possibilities. Scorsese is about making things true to life, not making people into symbols or representations of ideas, and it has served him well, but don’t we all react to stories as having messages, whether that was their original or primary intention or not? We leave the movie theater trying to sort out the implications about life of the tale we’ve just seen enacted, no matter how clichéd or obvious or unintentional the implications might be. We think and wonder about what the movie means. Even pure action films say something about the worldview of their makers.

But it’s also true that Phillips and Phoenix were specifically interested in treating Arthur Fleck as a real human being, fully dimensional, not a 2-D cartoon, and that, given Phoenix’s supreme abilities and Phillips’s sensibility and flexibility, was a huge benefit to the movie. Art Spiegelman’s Maus was a comic book too, a story about anthropomorphic cats and mice and pigs. Comics can be profound. I’m not making that claim for the Jokers, but they are worthy of being discussed in the same breath as Scorsese; they deserve that respect.

I am not a follower of super-hero comics-universe movies. In fact I broadly agree with Scorsese’s recent protests about them in general, as being more like amusement parks, theme parks, than films. But there are exceptions, and of the ones I’ve seen, the Batman-and-company entries are the most interesting. I don’t know why it worked out that way, and, since I haven’t seen a lot of them, maybe there are other good ones I’m unaware of. For sure, whatever else, I know I feel at home in the dark and slummy environs of the batperson’s Gotham City…

So, no, I wasn’t watching the movie as any kind of super-hero-media traditionalist or purist. I watched it as a simple moviegoer and humble cinephile, so it wasn’t grating to me that Joker/Arthur and Harley Quinn/Lee Quinzel (Lady Gaga) sang numerous duets, that the movie is a musical of sorts. I just got off on it, and all the more so for that refusal to be limited by traditional super-hero tropes. But more about the singing later.

Another major outrage of the movie that gives me a kick is how claustrophobic it is. It takes place mostly in a prison and a courtroom—being another example of Phillips’s defiance of propriety and expectations. You rightly expect spectacle from a $200M “Batman”-DC-Comics-World flick, but no, it’s all sweating walls and peeling paint and inescapable enclosures, depicted in that elaborate shadowy, vaporous, gray, dark-comic-book style. While still, being as it’s a noirish exercise, as few exterior shots as there are, there is plenty of pouring rain, one way or another.

And the movie opens with an actual animated cartoon in the style of the old Warner Bros. Looney Tunes. It stars Arthur transforming into Joker: “Me and My Shadow” foreshadowing the crux of the whole movie, along with Phillips’s and Phoenix’s determination to have the story and acting take seriously the humanity and psychological condition of Arthur Fleck.

Again, to me, the liberal intellectuals’ tendency to reflexively revile the film as cynical in its reveling in violence, is mistaken. Fleck’s misery is the misery of all the abused and dispossessed oppressed. The critics think he’s not supposed to respond in kind. To that I say that nations and societies are the mass equivalents of individuals. Societies fight furious wars all the time and they almost always feel justified in that, and nearly everyone acknowledges this, as unpleasant as it may be. So why should an individual who’s been consistently held down, attacked, and humiliated respond any differently? I’m not defending violence. I’m just saying that the messenger shouldn’t be blamed for the unpleasant truths.

And Phillips is an inspired director. The opening, squarish-shaped— 4:3 aspect ratio—animated cartoon presents Joker as the violent, amoral, literal shadow of the damaged aspiring stand-up comic Fleck, and, once that Looney Tune drama is played out in three minutes, with animated Arthur getting police night-sticked to a pulp for what has actually been the sins of Joker, the cartoon concludes by opening, as a curtain, on the actual widescreen prison where Fleck is being held following his arrest at the end of Joker I. The thing is that the material prison, the prison set, looks as much like a cartoon as the cartoon we were just watching, like a frame from, say, the interior of the castle of the wicked queen in Disney’s Snow White, or the darker parts of Pleasure Island in the Disney Pinocchio, as it looks like a real prison.

And the movie is full of moments that are primarily for aesthetic or intricately allusive purposes, rather than narrative per se, though of course anything whatsoever presented in a movie does also support the story, since whatever the audience sees affects their reading of the narrative to some degree. But I’m just saying, this is a movie made by artists, not merely journeymen amusement park designers, or exploitation filmmakers. One shot I loved was part of a brief sequence of four prison guards escorting Arthur across the grim enclosed psychiatric-prison’s pavement yard in the rain under their dark umbrellas. And then we see, suddenly from thirty yards above, the broad floating disks of the four umbrellas held by the guards, but now gorgeously tulip-hued: one umbrella red, one blue, one yellow, and one tan, floating in a square, symmetrical formation, Arthur exposed unsheltered in the middle. This lyrical moment seems gratuitous, done just because it looks great. I don’t know what other meaning it could have. Wait! I just Googled and learned that those are exactly the colors of Joker’s outfit in the first flick. Which are also the colors of his suit in the opening cartoon. It’s as if Joker is the only bright color in Arthur’s dreary confinement.

Or take, say, the wild, irresistibly endearing choice to cast as the judge at Joker’s capital trial a Martin Scorsese look-alike.

The movie is a continuous stream of such as these interwoven openings-out into further extrapolations. Every moment of it has been considered by its makers for its possibilities of communication from within the parameters of itself, and even beyond them into the meta as well as the backstory of the film’s creation. It’s rich and complex.

I should also point out that Phillips’s directorial history, being most strikingly the great blockbuster comedies Old School and the three Hangover movies, in fact commenced with a feature-length documentary called Hated that he made at the age of eighteen in film school at NYU, which in fact went on to be an historically exceptional box office success for a student film, and the subject of it was the viciously violent and literally shit-smeared, naked-on-stage-at-times, ultra-aggressive punk rock musician GG Allin, who after the filming died almost immediately of a heroin overdose in Phillips’s presence. The director has a background of knowing interest in anger and aggression acted out by an abused underclass. The documentary contains scenes revealing the horrific environment Allin endured as a child, including that his father tried to persuade the family to commit suicide together.

So, back to the songs in the film. As dark as it is, the movie is exuberant. I understand that the more comic-book oriented DC movie fans hated the singing as a betrayal of the form, the values, of super-hero movies, but, to me, the songs and their performances were revelatory. Not only were the songs brilliantly chosen for how they fit and spoke to whatever the situation was with Gaga’s Lee and Phoenix’s Arthur/Joker at given junctures in the twisted love story, but the performances worked exquisitely, movingly, by way of the actors’ phrasing and use of the melodies, but also because their acceptingly quasi-amateurish delivery brought the words to the fore. Then there’s the marvelous dancing of the pair, Phoenix’s especially expressive. Because of this beautifully conceived and calibrated approach to lyrically showing and telling their story, I felt the emotional and narrative import of the familiar Great American Songbook standards more than I can remember feeling them in the most talented traditional performances I’ve heard, outside of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. They definitely outdistanced Frank and Barbra. In fact, I’d like to end this essay with the lyrics to what worked out to be a kind of meta theme song for the flick, even though it sort of renders all my chatter here extraneous:

That’s Entertainment!2

Everything that happens in life

Can happen in a show

You can make 'em laugh, you can make 'em cry

Anything, anything can goThe clown with his pants falling down

Or the dance, that's a dream of romance

Or the scene where the villain is meanThat's entertainment

The lights on the lady in tights

Or the bride with a guy on the side

Or the ball where she gives it her allThat's entertainment

The plot can be hot, simply teeming with sex

A gay divorcée who is after her ex

It can be Oedipus Rex

Where a chap kills his mother and causes a lot of bother

The clerk who is thrown out of work

By the boss who is thrown for a loss

By the skirt who is doing him dirt

The world is a stage

The stage is a world of entertainmentThat's entertainment

That's entertainment

The doubt while the jury is out

Or the thrill when they're reading the will

Or the chase for the man with the faceThat's entertainment

No death like you get in Macbeth

No ordeal like the end of Camille

This goodbye brings a tear to the eyeThat's entertainment

Admit it's a hit and we'll go on from there

We played a charade that was lighter than air

A good old-fashioned affairAs I sing this finale I hope it's up your alley

The gag may be wearing a flag

That began with a Mr. Cohan

Hip hooray! The American way

The world is a stage

The stage is a world of entertainment

From an interview with Phillips by Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air: “So it's this flexibility I've always had with story that I think is what made me transition to working with somebody like Joaquin so kind of seamlessly. [...] I jokingly always say filmmaking is not math. It's jazz, meaning it's a living, breathing organism that is constantly changing shape.”

Lyrics by Howard Dietz

I did not expect to get persuaded to watch this movie, but Richard did it.

Loved this.